And There Were None proves Christie's works remain a timeless classic: Theatre review

And Then There Were None directed by Lucy Bailey debuted in Richmond this month

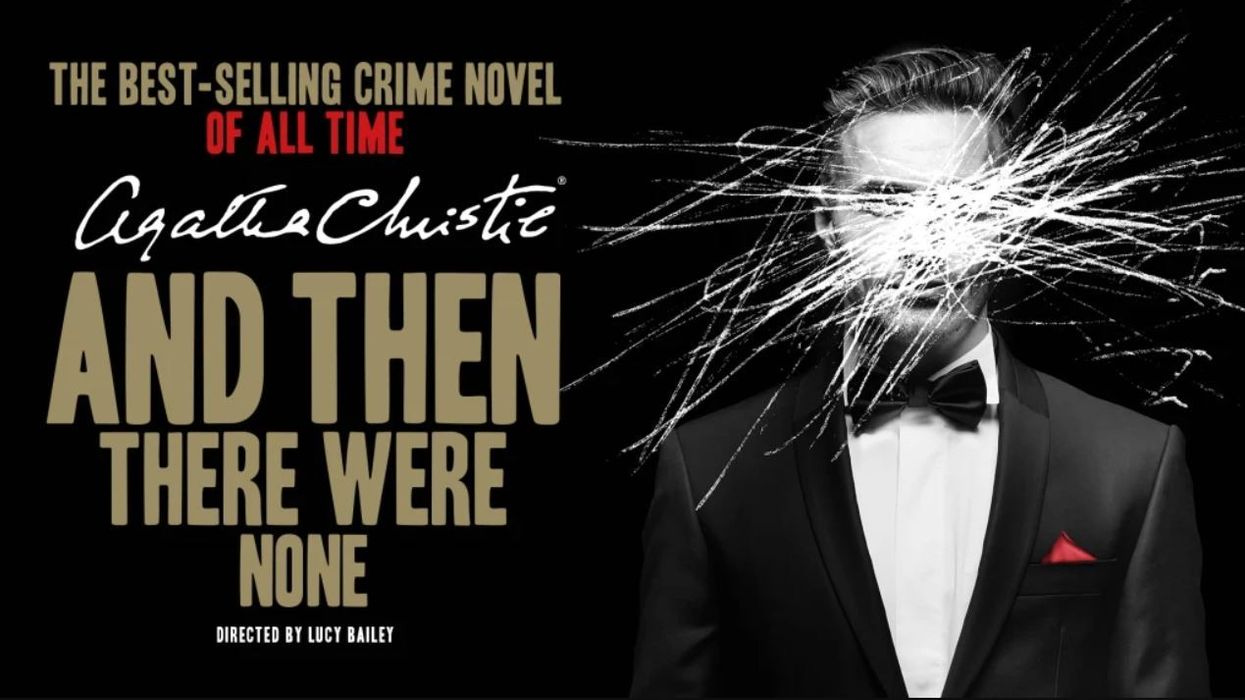

|AND THEN THERE WERE NONE

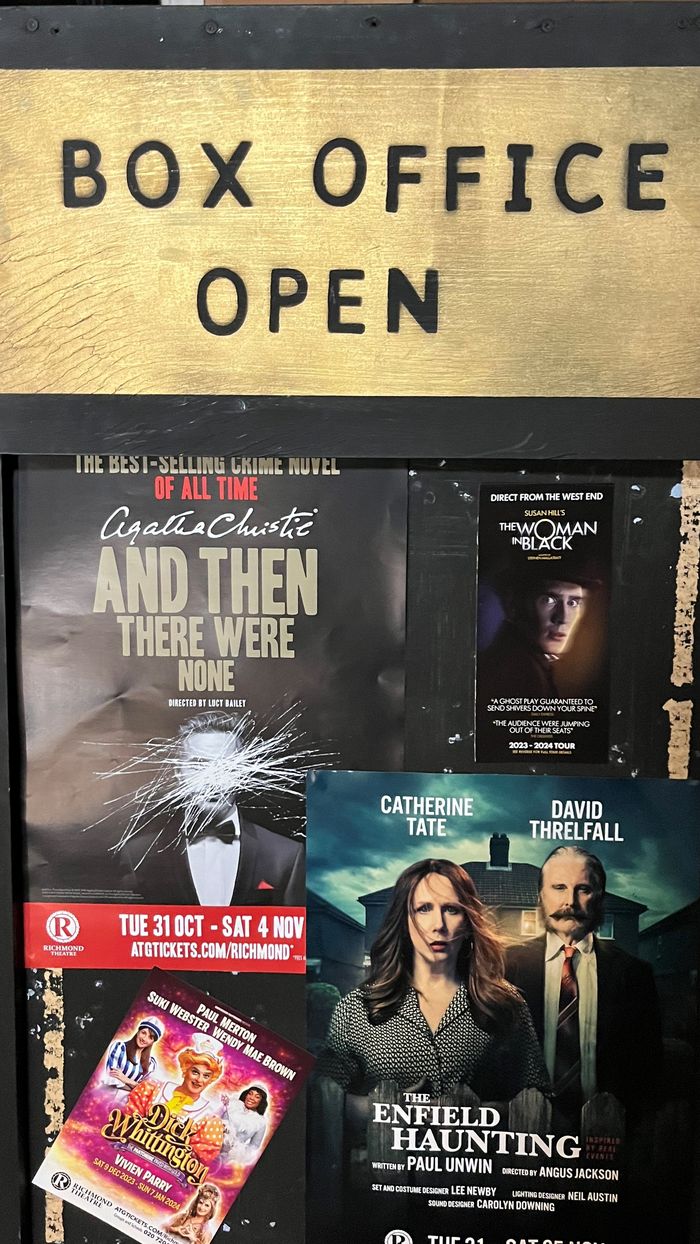

And Then There Were None debuted at the Richmond Theatre this month

Don't Miss

Most Read

Agatha Christie loved nursery rhymes. Fact. ‘Three Blind Mice’ is one of the structuring forces behind her play The Mousetrap, the world’s longest-running theatre show in history.

It is no surprise, then, that her book And Then There Were None - the best-selling crime novel of all time - is punctuated throughout by the poem ‘Ten Little Soldier Boys’.

Despite the novel’s undeniable theatricality, we haven’t seen a large scale stage adaptation of And Then There Were None before - until now.

Christie’s work has never really gone out of fashion, although in recent years her stories have had a somewhat noticeable revival. The transformation of her short story Witness for the Prosecution into a play in 2017 has been immensely successful.

Directed by Lucy Bailey, and staged at the stunning County Hall, London, Witness is an incredible example of how flexible Christie’s writing is - a short story of roughly 15 pages long thrives as a two hour play in such an iconic setting.

Christie’s work was predominantly catapulted back into mainstream culture via Sarah Phelps’ television adaptations which began in 2015. Since then, Kenneth Branagh’s take on Poirot has divided critics, something particularly illustrated by his new film A Haunting of Venice, which is not an original Poirot story.

So when I heard that Lucy Bailey - who, aside from her work on Witness, directed perhaps the most impressive take on Titus Andronicus at The Globe in 2014 - was behind this new theatrical adaptation of And Then There Were None, I was very excited.

There is no doubt that this was the best way to spend my Halloween evening: above all, I’m so surprised that we haven’t seen a large-scale theatre production of And Then There Were None before, because the plot is simply steeped in melodrama.

And Then There Were None premiered at the Richmond Theatre earlier this month

|KATIE BOWEN

As 10 strangers are invited to Soldier Island by the mysterious Mr and Mrs U. N. Owen (can you already spot how clever Christie is?), mayhem ensues when an announcement is played out over a gramophone accusing each person of committing heinous crimes.

What unravels next is a murder mystery plot that seems to defy logic - but, as always, Christie has the perfect solution.

Given how the story is set up, we are constantly shifted between the present moment and the past lives of these 10 characters; Chris Davey’s lighting design signalled this movement clearly.

When we looked back at some of the characters’ memories, soft, warm, yellow hues illuminated the stage - in moments of violence, though, the space was plunged into icy blue light.

During the scene in the second act when the final four really do begin to lose their minds (references to animals and unchecked desire made this feel Lord of the Flies-esque), spectacular flashes of red light lit up the stage, emphasising the thrilling, reckless behaviour of those left on Soldier Island.

Just as the plot itself moves between background and foreground, set designer Mike Britton’s fascinating layout physically indicated this split focus. Throughout the play, a sheer curtain effectively split the stage in two, forcing the action to predominantly occur at the very front of the playing space.

Not only did the movement of this curtain mimic the rolling waves of the sea - the island setting in the story is, of course, of the utmost significance - but the haziness of what was happening behind the curtain added a sense of intrigue.

While this stood as a reminder of the often unclear and mysterious memories that haunt the ten people on Soldier Island, it principally allowed the audience to become agents in the action, as we became detectives ourselves when attempting to decode what was going on slightly out of sight.

Often, it was behind this curtain that the memories of characters like Emily Brent and General Mackenzie were acted out. Here, past and present events were placed in near proximity, only separated by a thin piece of fabric; this cleverly suggested to the audience just how closely past events were coming to bear on the present action.

This sense of involvement and scrutiny for the audience was obvious at the start of the play. It began with a tableau of all of the characters who were spotlighted one-by-one as their invitation to Soldier Island was revealed. The dinner scene in the first act created a similar moment, with the actors going into slow motion behind the sheer curtain.

In a play all about judgement and the law, these tableaux struck me as an opportunity for the audience to exercise their own judgement of each character unapologetically. Other elements of the staging also tied into this legal theme.

A large section of the stage sloped, effectively creating a ramp which the characters climbed (and slipped) up and down. Here we had that notion of ‘weighing up the evidence’ literalised on stage - there was a lack of balance which naturally destabilised the characters as they walked around, exacerbating And Then There Were None’s concern with justice and balancing out right and wrong.

In terms of individual performances, Sophie Walter as Vera Claythorne was exceptional. What really stood out was not only how there really seemed to be strains of other Christie women filtering through into her character - Tuppence from the Partners in Crime series, or Miss Caswell from The Mousetrap perhaps - but also how Claythorne navigated her role as a woman in a crowd mostly made up of men.

That can get forgotten when reading the novel; on stage, though, the pull Claythorne has in the group becomes noticeable and powerful in Walter’s performance. Domesticity is another key theme of the play that is stressed by Walter. The dining table sits quietly behind the curtain in Act One, although in the second act it is moved to become front and centre.

The mess and destruction that goes on around - and on - the table during Act Two perfectly symbolises how the veneer of society that initially brings these characters together slowly erodes.

That Vera is at the forefront of this chaos emphasises the challenge to the traditional domestic image Christie proposes here. Other performances to mention include Joseph Beattie as Phillip Lombard.

Beattie had the perfect amount of suaveness, arrogance and humour to fashion Lombard into the Marmite figure he needed to be in this large group. Lucy Tregear as Rogers was also brilliant; Tregear managed to create different moments of contrast in the character which was interesting.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS:

- Carol Vorderman QUITS BBC in fury at new social media rules as she fumes 'I’m not prepared to lose my voice'

- Amy Dowden says cancer treatment will last 5 years as star left 'gutted' ahead of major milestone

- BBC Strictly fans 'work out' next dance-off pair as they rage at 'cursed' routine choice for two stars

And Then There Were None proved a success to sellout crowds at Richmond Theatre

|KATIE BOWEN

There were so many other things that excited me about this production: Britton’s set design created even further depth besides the sheer curtain, as the dead characters returned to stand at the very back of the stage, partially obscured, towards the end of And Then There Were None.

This, coupled with the painted blue waves around the stage, reminded me of Henrik Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea. The emotion and despair that power this play struck me as an interesting overlap to Christie’s story. Ibsen’s play is also preoccupied with past secrets, and strangers lurking at the boundary points of the stage.

There’s probably not much in this comparison except for Vera’s similar anxiety with the ocean that Ellida Wangel has in Ibsen’s drama. It just goes to show, though, how by freshly reimagining Christie, her writing continues to participate in conversations with literature from across the span of time.

The work of sound designer Elizabeth Purnell also deserves a mention - in particular, the haunting sound that accompanied Vera Claythorne’s memories had a sing-song-like effect which paired well with the ‘Ten Little Soldier Boys’ poem that is at the heart of this story.

A brief note on the ending: Bailey does not hold back, and her choice to follow the story right through to its original conclusion is bound to be controversial. I am pretty strongly against having trigger warnings for all forms of art. For me, it takes away from what exactly theatre, literature and any other form of cultural interaction is meant to do. These things are meant to shock and surprise, confuse and upset, anger and cheer up.

While the final scene was very graphic, I did check on the Richmond Theatre website, and those who wanted additional information about the themes the play confronts could readily access them. I think this is how trigger warnings should be done - there was ample information available on the website before the performance for those audience members who wanted to be forewarned about specific events, but this wasn’t at the detriment of the whole audience which left the breathtaking shock intact.

Lucy Bailey’s direction of And Then There Were None proves how effortlessly Christie’s stories leap from page, to stage, to screen; the strength of narrative and characterisation illustrates just how flexible her writing is. That Christie is so successful across literary genres is testament to her enduring influence as a novelist and what she continues to achieve almost 50 years after she died.

And Then There Were None is touring throughout the country for the rest of this year and into 2024. Find tickets and your nearest venue here: https://andthentherewerenoneplay.com/