The benefits bust-up overlooked a very inconvenient truth. One that will soon sink Labour - Hilary Salt

GB

The regional split of disability payments with concentrations in the de-industrialised regions is telling

Don't Miss

Most Read

Trending on GB News

On Tuesday, the Government abandoned almost all its proposals to cut disability benefits after an effective rebellion by backbench Labour MPs. It was hard to keep up with the Government’s position as initial proposals came tumbling down in what one Labour backbencher described as being “incoherent and shambolic” and “the most unedifying spectacle I have ever seen”.

How did the Government manage to get to this position? It’s reasonable to say that almost everyone agrees that the vast and growing amount spent on disability benefits (around £40bn in 2023/4) is a problem, as is the reduction in the workforce (over four million) caused by this. The question is: what to do about it?

When the Chancellor announced significant cuts to disability benefits, she appeared to be thinking only of the savings available – I’ve referred to her before as the “goal-seek” Chancellor – just get the spreadsheet to give the right answer, don’t worry about the political rationale or practical implications.

It was left to Liz Kendall, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, to try to justify the move. She did this with what felt like sincerity (“there’s nothing compassionate about leaving millions of people who could work without the help they need to build a better life”) and determination – defending the policy even as the Prime Minister was organising a climb down.

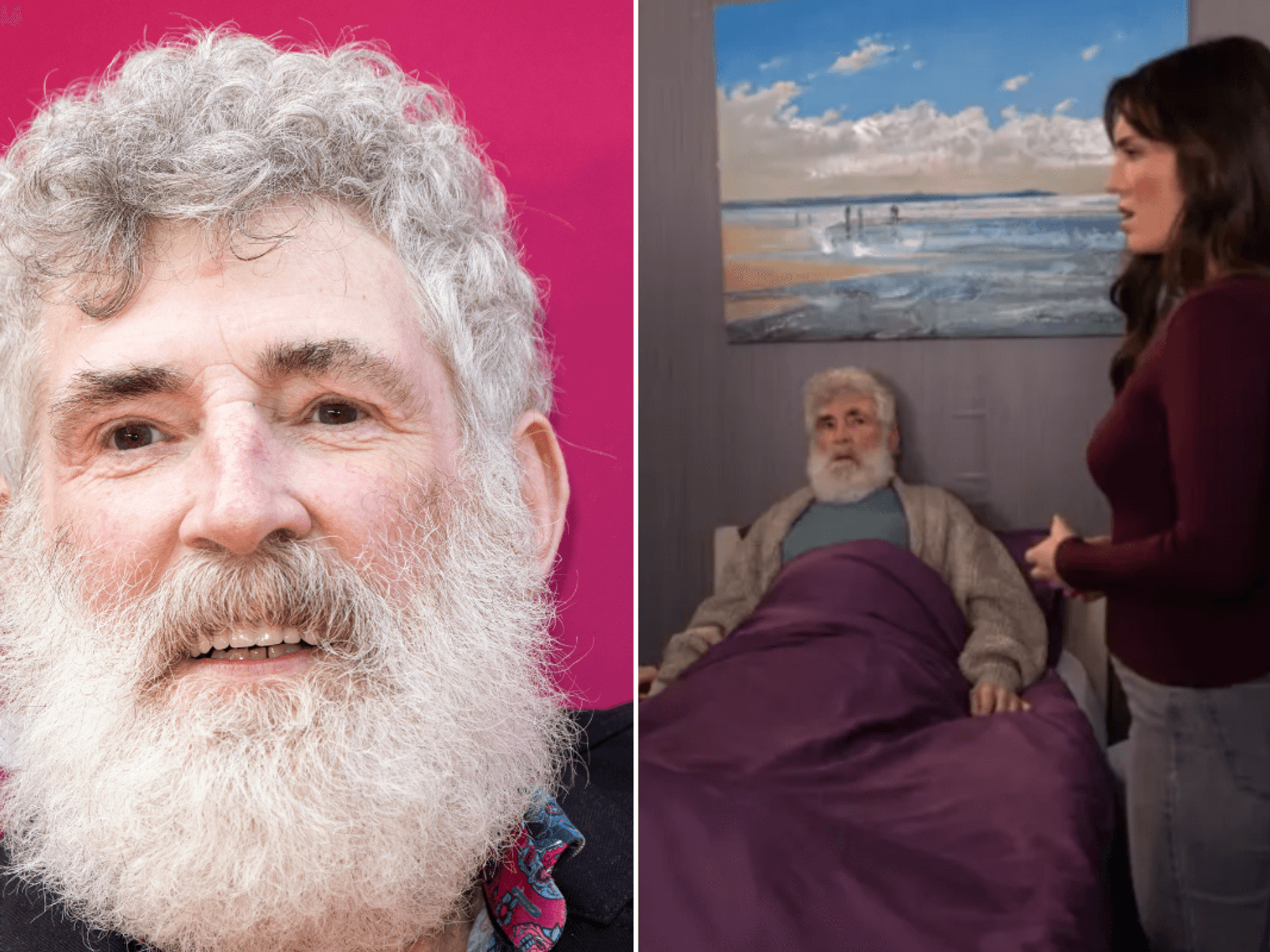

The benefits bust-up overlooked a very inconvenient truth. One that will soon sink Labour - Hilary Salt

|Getty Images

Some revision of the proposed policy was needed – it would have sucked millions of pounds out of many of the old Labour heartlands without those areas having any new industries to provide employment. And the proposals made no real investment in supporting people into work.

That regional split of disability payments with concentrations in the de-industrialised regions is telling. Of course, this is in part because poverty and the effects of manual labour cause ill health and there may also be some disguised unemployment.

But it is also the case that these regions have lost the strong identity and community respect attached to the old industries. Whilst avoiding romanticisation, there was a real dignity in being a steel worker, an engineer, or a textile worker. It’s difficult to see the same value in work in a call centre or hospitality – or even some of the higher-paid roles in HR or IT.

The lack of any prestige or personal identity in work has led to “the corrosion of character”. When work is just something you do to get paid, there is no feeling of being part of the team, wanting to go above and beyond, so signing off on the sick doesn’t have the stigma it used to.

The camaraderie of working together has fallen further with working from home – you don’t build resilient work relationships with people you only see online.

This is perhaps why so many people are willing to accept the identity of being long-term sick. To address that, we need massive investment across the country and the creation of meaningful, rewarding well paid jobs that make claiming disability benefits a clearly inferior option.