Mystery of 'little red dots' in space is solved as astronomers confirm 'violent forces' at hand

The strange dots vanished without explanation around 12 billion years ago - and scientists now think they know why

Don't Miss

Most Read

Latest

Scientists at the University of Copenhagen have cracked one of astronomy's most puzzling riddles.

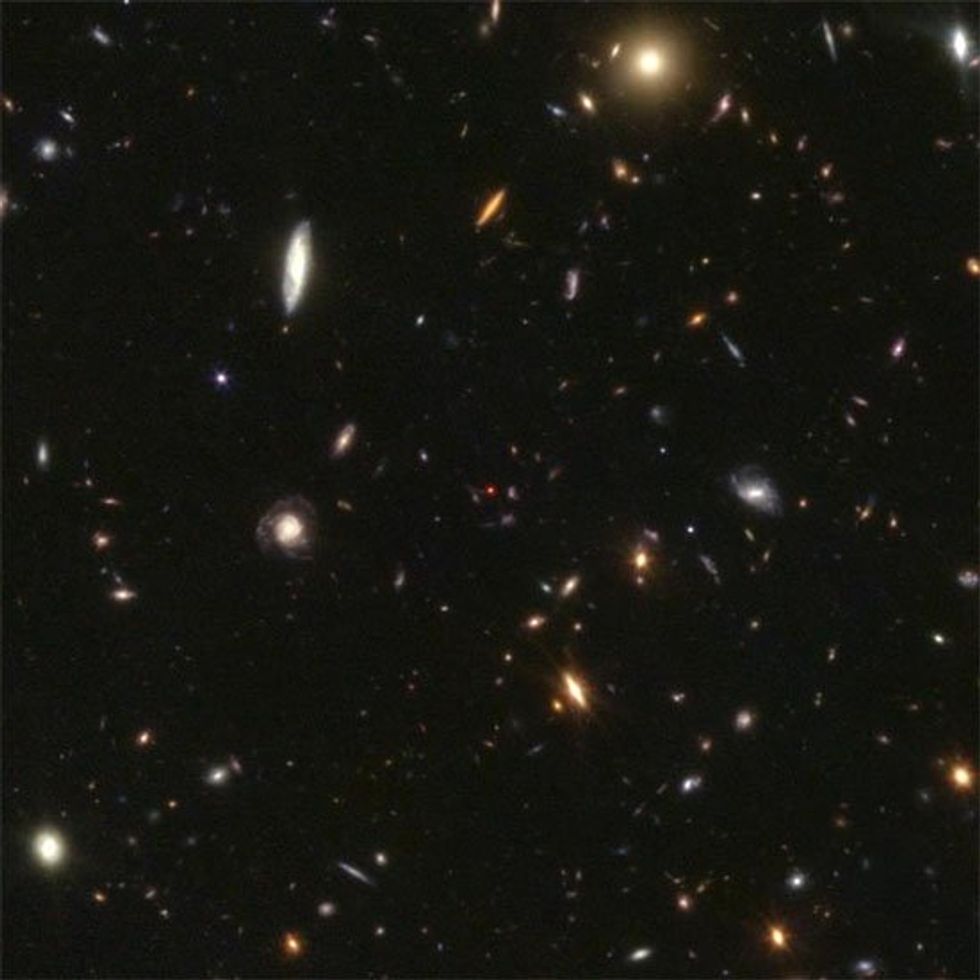

A series of mysterious "little red dots" first emerged in telescope images of the universe as it looked 13 billion years ago.

They then mysteriously vanished approximately one billion years later.

Initially, astronomers suspected these faint lights were infant galaxies in their earliest formation stages.

But this theory clashed with our understanding of the universe following the Big Bang - the very first galaxies should not have been visible until much later in the universe's history.

An alternative hypothesis suggested the dots were black holes, created when massive stars collapsed.

Yet this explanation also posed difficulties.

Researchers struggled to account for how any black hole could have grown large enough to produce a red dot so soon after the universe began.

Now, fresh analysis of images from the James Webb Space Telescope has found that they are are young supermassive black holes, according to research published in the journal Nature.

A series of mysterious 'little red dots' first emerged in telescope images of the universe as it looked 13 billion years ago

|JWST/DARACH WATSON

These ancient objects - dubbed "the most violent forces in nature" - are shrouded in "cocoons" of ionised gas.

As the black holes consume material from their surroundings, the swirling matter generates immense heat and radiation.

This energy shines through the gas cloud, creating the distinctive red appearance.

"We have captured the young black holes in the middle of their growth spurt at a stage that we have not observed before," said lead author Professor Darach Watson.

Prof Watson's research reveals these black holes are far smaller than scientists had previously calculated.

SPACE MYSTERIES - READ MORE:

'We have captured the young black holes in the middle of their growth spurt,' Prof Watson said

|JWST/DARACH WATSON

"The dense cocoon of gas around them provides the fuel they need to grow very quickly," he explained.

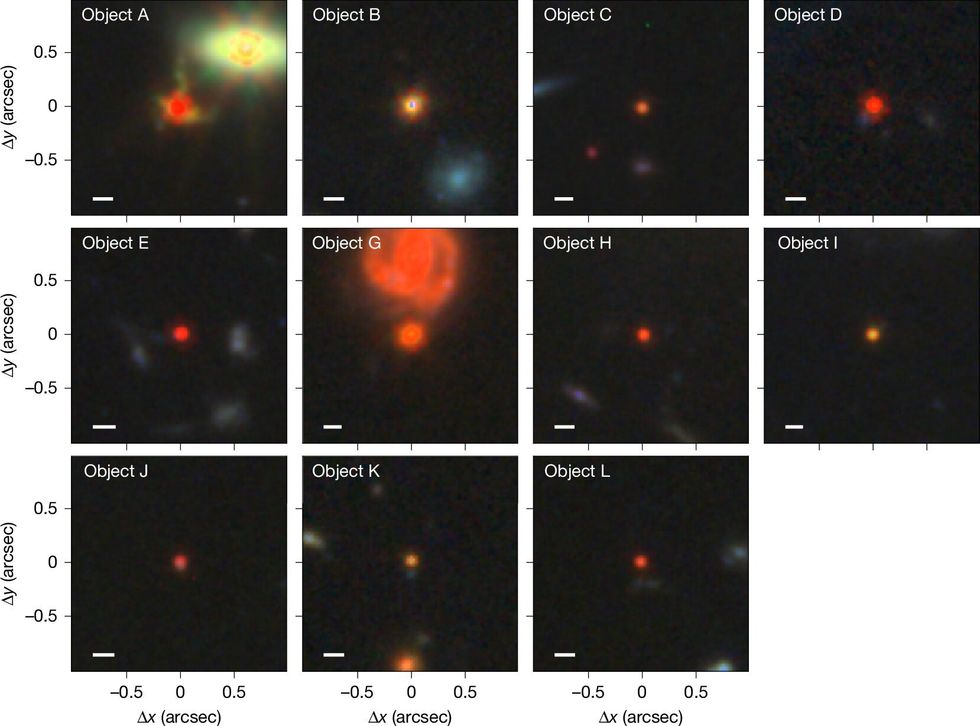

The team analysed spectral emission lines from several little red dots, finding much of the UV and X-ray radiation was missing.

This confirmed the light was passing through a gas cloud.

"When gas falls towards a black hole, it spirals down into a kind of disk or funnel towards the surface of the black hole," Prof Watson said.

New analysis offers fresh insight into how enormous black holes emerged so rapidly in the early universe

|JWST/DARACH WATSON

"It ends up going so fast and is squeezed so densely that it generates temperatures of millions of degrees and lights up brightly."

The findings offer fresh insight into how enormous black holes emerged so rapidly in the early cosmos.

These young black holes are consuming gas at rates approaching the maximum theoretical limit, known as the Eddington Limit.

"We found that the black hole masses are 10 to 100 times smaller than previously supposed, and that they are accreting gas at the limit, so these facts ease up very much on the problem of how they grow so fast," Prof Watson continued.

But despite being smaller than expected, these objects are up to 10 million times larger than the sun.