Dirty secrets of ancient Rome uncovered by archaeologists in Pompeii

The city's inhabitants lived remarkably filthy lives until Emperor Augustus intervened

Don't Miss

Most Read

Scientists have shed new light on the dirty habits of ancient Rome in Pompeii.

By taking a look at limescale in the destroyed Roman city, researchers have found how its ancient inhabitants took extraordinarily filthy baths.

The chalky residue found on the city's wells, pipes and bath walls has revealed how water flowed through Pompeii before Mount Vesuvius destroyed it in 79 AD.

The oldest baths "did not meet the high hygienic standards usually attributed to the Romans," said Dr Gul Surmelihindi of Johannes Gutenberg University in Germany, who led the study.

Dr Surmelihindi and her colleagues examined the Republican Baths, constructed in the second century BC.

Threy discovered that bathwater was reused over and over again before the Pompeians finally built an aqueduct.

This led to heavy contamination from sweat, skin oils, urine and other bodily waste.

These facilities predated Pompeii's formal absorption into the Roman Empire.

The baths continued operating into the early first century as the city became increasingly Roman.

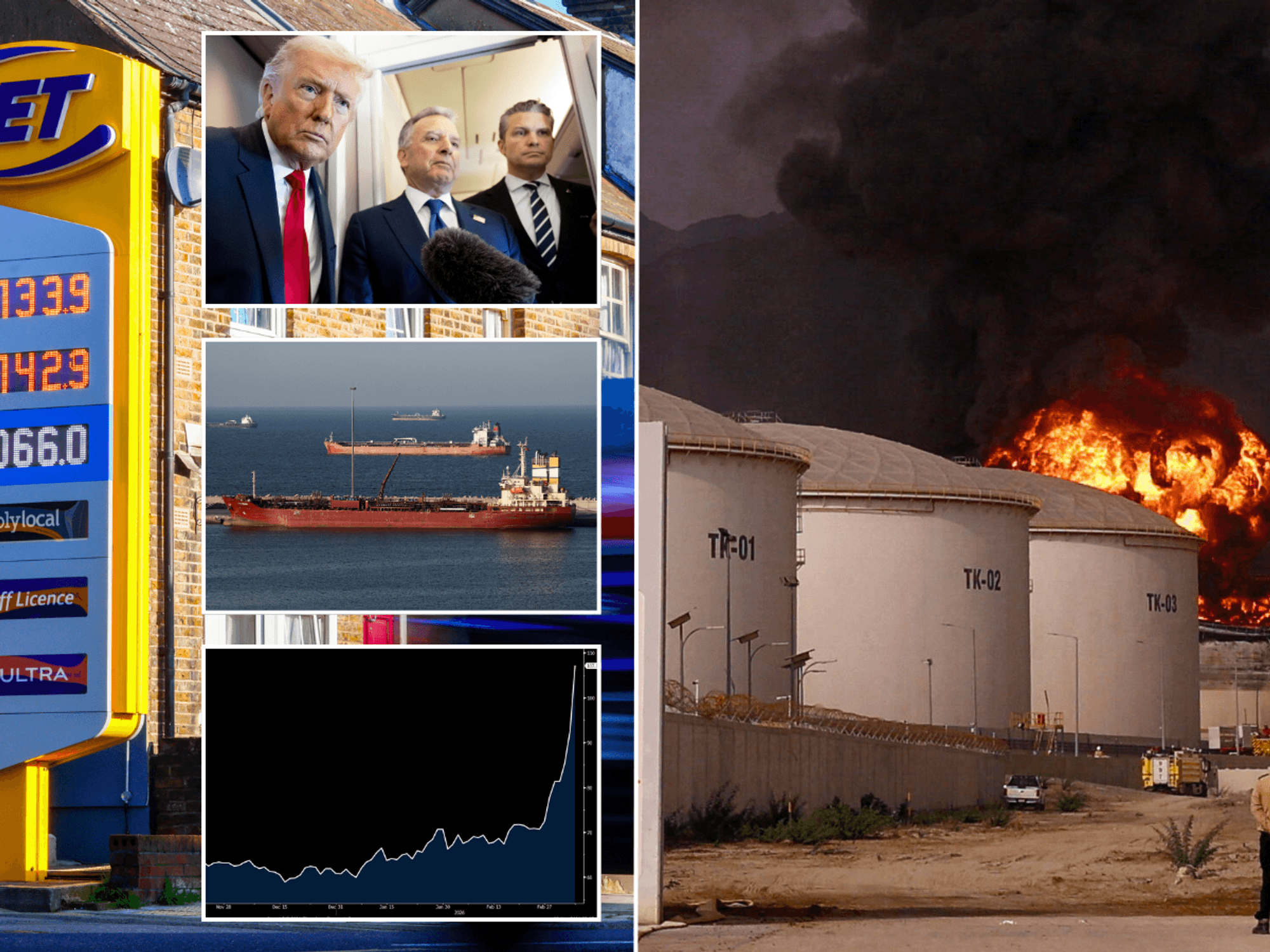

PICTURED: The Stabian Baths - the oldest thermal baths in the archaeological site of Pompeii

|GETTY

Limescale proved crucial to the investigation.

The mineral deposits accumulate in layers over time, similar to tree rings.

Carbon atoms become trapped within these crusty formations.

These atoms record when organic materials entered the water supply.

Human waste products leave a distinct chemical signature.

ROMAN MARVELS - READ MORE:

By studying deposits from wells, pools, drains and the aqueduct, researchers tracked water quality changes throughout the system.

Pompeii lacked a nearby river for its water needs.

The city depended on wells dug more than 30 metres underground for centuries.

Slaves operated treadmill devices to haul water to the surface.

This gruelling process severely restricted supply.

By studying deposits from wells, pools, drains and the aqueduct, researchers tracked water quality changes throughout ancient Pompeii

|GETTY

Public baths could only refresh their pools once daily at best.

Some facilities may have changed their water just once every two days.

Carbonate deposits showed dramatic shifts in carbon isotope levels between wells and bathing pools.

The drains revealed even greater changes.

Researchers attributed this pattern to accumulated human waste: sweat, oils, ointments, urine and the microbes that fed on them.

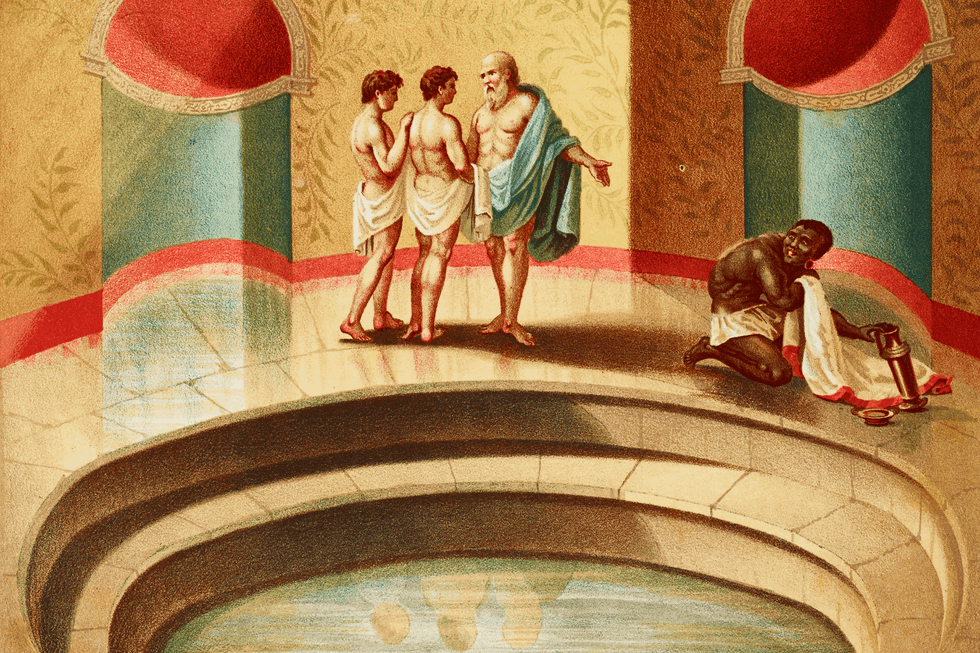

PICTURED: An artist's impression of life in Pompeii's bathhouses - after they cleaned up their act

|GETTY

Lead contamination also posed a risk as water passed through the city's lead pipes.

However, limescale buildup eventually coated the pipes' insides, reducing metal release over time.

Conditions improved significantly in the first century AD.

Emperor Augustus connected Pompeii to a major Roman aqueduct system.

Fresh spring water began flowing from the Apennine Mountains, delivered by gravity rather than muscle power - and supply increased dramatically as a result.

Limescale deposits from this later period appear thinner with distinct chemical properties, and show far less evidence of organic contamination.