Now Reform has the momentum, it must unlock five doors to enter the corridors of power - Miriam Cates

OPINION: Reform can no longer be dismissed as a protest movement, but winning power is a marathon not a sprint

Don't Miss

Most Read

Latest

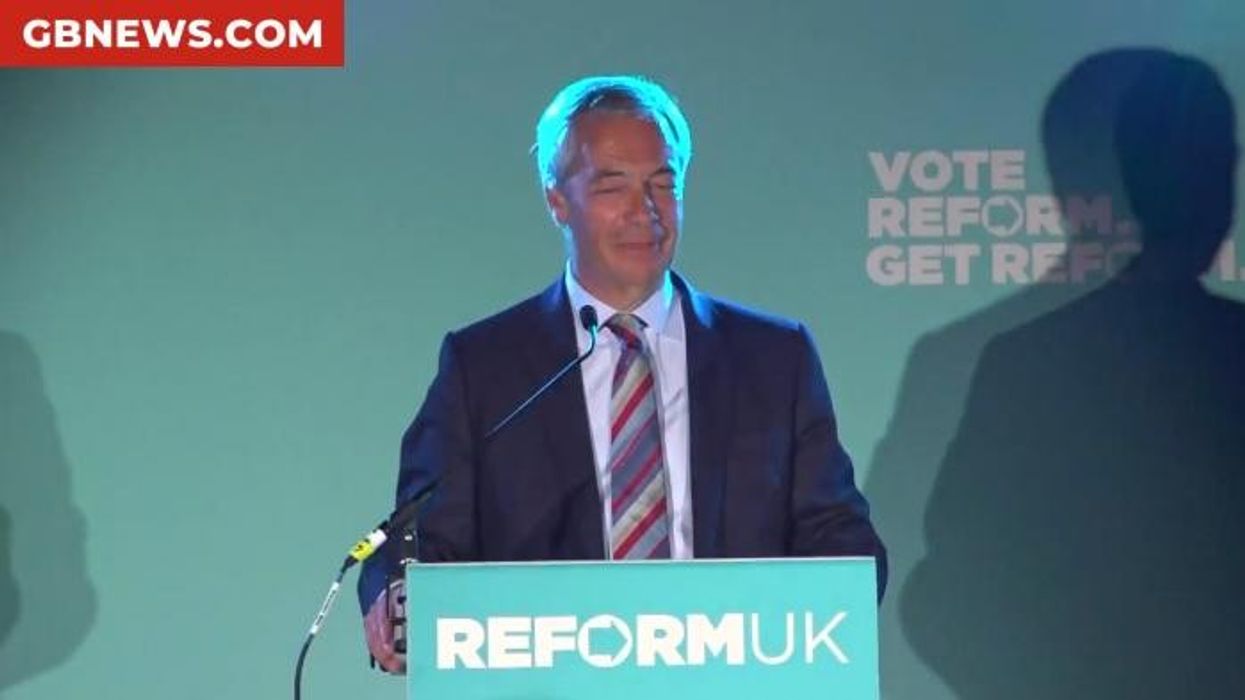

This week, Reform UK finally had the chance to prove whether their recent poll leads could be converted into real votes and real power. And Farage’s Party has certainly lived up to his own confident predictions of success, winning the Runcorn Helsby parliamentary by-election by six votes and the Lincolnshire mayoralty by a landslide.

Even in areas where they were thought to have slim chance of winning, Reform ran the Labour party close, such as in the mayoral elections in Doncaster and North Tyneside.

Reform’s Arron Banks even finished in second place to Labour in Bristol and the West of England, an election that was widely believed to be a two horse race between Labour and the Green Party.

The days of two party politics are over, with Reform now seemingly in contention for a huge number of seats at the next general election. Indeed, if the swing from Labour to Reform in Runcorn (17 per cent) is extrapolated across the 650 parliamentary constituencies in 2029, the insurgent party could win over 400 MPs. At the time of writing, both the Conservatives and Labour have suffered sizeable defeats in the local council elections. Reform picked up the lions share of these seats, but the Liberal Democrats also benefited from the collapse in support for the two old parties.

Over the next few days, many column inches will be devoted to analysing the results of these elections, and both the Conservative and Labour Parties have already begun trying to justify their heavy losses. The Conservatives point out that it is too soon for the public to have forgiven the Tories for failures in government and the Labour Party claim they need more time for the electorate to feel the ‘positive impact’ of the policies of the new Labour government.

Reform UK currently has all the momentum, and the party seems likely to capitalise on this at the next general election. The issues that have caused voters to reject the established parties – immigration, inflation, strained public services – show no sign of being fixed, leaving an open door for Nigel Farage and his colleagues.

But as we have seen over the last decade, politics in the UK, and indeed across the West, has become turbulent and unpredictable. Fifty years ago, it was common for voters to demonstrate lifelong loyalty to one party, yet now people are much more likely to change their vote at each election in response to which party, candidate or leader best reflects their views.

This loss of long-term party alignment has thrown up some extraordinary results. Who could have predicted that the Conservatives would have gone from one of their biggest historic victories in 2019 to their worst ever loss in just four and a half years? Or that Labour could win a landslide victory on a vote share of just 33.7 per cent? In Europe, right wing populists have defied expectations, yet in Canada, the Liberal party overturned a 20 point poll deficit in just a few months. The only thing that’s predictable is that politics is now unpredictable; many things could change before the next election.

Aside from the opinion polls there will be a number of interesting things to watch over the coming months and years in British politics. Here's my rundown of the five bellwethers from now until 2029 that will signal Reform could become the party of government.

1) How will the Labour Party respond to the swing to Reform?

The loss of so many Labour voters to Reform in the ‘Red Wall’ will worry Labour HQ. Should last night's results be repeated on a national scale, many cabinet ministers would lose their seats and there would be no prospect of the Labour Party winning a second term in government.

Yet even in the aftermath of these elections, Sir Keir Starmer and other senior labour figures seem already to be taking the wrong message entirely from Thursday's drubbing at the ballot box, claiming that they just need ‘more time’ for their plans to come to fruition. But surely the message sent by the electorate (just 15 per cent of whom voted Labour this week) is clear: many people are not impressed with Labour’s ‘plans’.

They want the Government to be tougher on immigration, drop unaffordable Net Zero commitments and bring taxes down rather than up.

There are some in the Labour movement who understand this and so we may see Labour tacking to a more common sense position on these issues. Could that be enough to win back disenchanted Labour voters from Reform?

2) Will the Conservatives seek to do a deal with Reform?

Unless something extraordinary happens, it seems unlikely that the Conservative Party could win an outright majority at the next election. Yet as a result of the first past the post (FPTP) electoral system, and the uneven way in which support for each party is spread across the country, the Conservative Party could prevent Reform from taking power. Given that both the momentum and poll leads currently lie with Reform, any deal or informal agreement would be far more in the interests of the Tories than Reform. But when the election draws near, will Reform’s determination to topple Labour outweigh their reluctance to work with Conservatives?

3) What role will tactical voting play?

In countries that use a proportional representation system, there is no need for tactical voting. Electors vote for their party of choice, and each party is allocated a number of seats in proportion to the percentage of votes they receive. If no one single party achieves a majority, negotiations take place to form a coalition. Yet in FPTP, the only thing that counts is which party gains the most votes in each constituency.

It doesn’t matter if a party wins a seat by one vote or 40 000 votes, the party still only gains one seat in parliament. This system incentivises people to vote negatively, ie. to vote for the party that is most likely to defeat their least favourite candidate. So in a constituency like Sheffield Central for example, if you want to get rid of Labour, you should vote Green.

In Barnsley West, you should vote Reform. Parties on the left have successfully employed tactical voting for many years to minimise Tory wins, but the fracturing of left wing coalitions by sectarian candidates threatens its effectiveness. It will be interesting to see if voters on the right are willing to vote in equal measure for the Tories or Reform in order to oust Labour. Whichever side shows more willingness to vote tactically will be most likely to make big gains.

4) How will Reform UK manage the challenge of power in local authorities?

Until now, the Reform Party has had little in the way of political power and no mechanism through which to prove their competence or otherwise as a party of government.

After this week’s elections, Reform mayor Dame Andrea Jenkyns will be responsible for transport and policing and more in Lincolnshire, and Reform UK now controls several county councils. Local authorities operate under severe budgetary constraints, with around 80 per cent of their expenditure committed to statutory services such as adult social care. This means that in reality, individual councillors have limited power to drive significant local change.

If rate payers are dissatisfied with the performance of Reform held councils, could this dent Farage’s chances at the general election? Could the anti-establishment Reform UK be in danger of becoming an ‘establishment’ party?

5) Will any party tell the truth about the problems facing Britain?

So far, much of Reform’s electoral success can be attributed to the fact that they alone have been willing to take a common sense position on immigration that resonates with the public. Alhough Conservative MPs like Robert Jenrick have now become much more robust on the issue, thanks to the poor record of the last Conservative government and the even worse performance of the new Labour administration, voters are understandably reluctant to trust either the Tories or Labour on border control. But on other issues – such as the real reason for Britain’s terrible economic outlook, and the difficult decisions that will have to be taken to improve it – none of the major parties seem willing to say the hard things out loud.

Britain is in the midst of a severe demographic winter. Thanks to chronic and falling low birth rates, the ratio of 20 year olds to 60 year olds has halved since 1985, and this more than anything else is responsible for stagnant growth, and the rising cost of the state. When those on the verge of retirement outnumber those entering the workforce, it is simply not possible to achieve meaningful economic growth.

Cutting bureaucracy or axing diversity budgets are a drop in the ocean compared to the locked in and rising costs of pensions and healthcare. As a result of an aging population, the UK’s debt to GDP ratio is forecast to reach 270 per cent by 2070.

There is very little we can do about this in the short term, yet all the political parties claim they can ‘fix the economy’ or ‘boost growth’. It will be interesting to see if any of our political leaders are brave enough to start this conversation with the public before the next election.

For the impartial observer, this is an exciting time in UK politics. But for those involved in working for political parties or standing for election, living through the turbulence and uncertainty is deeply unsettling. Spare a thought for those brave—or stupid—enough to make politics their life’s work.