Mysterious blobs of hot rock around Earth’s core 'instrumental' in producing planet’s magnetic field

Researchers have been unable to determine the blobs' exact composition and characteristics due to their extreme depth

Don't Miss

Most Read

Latest

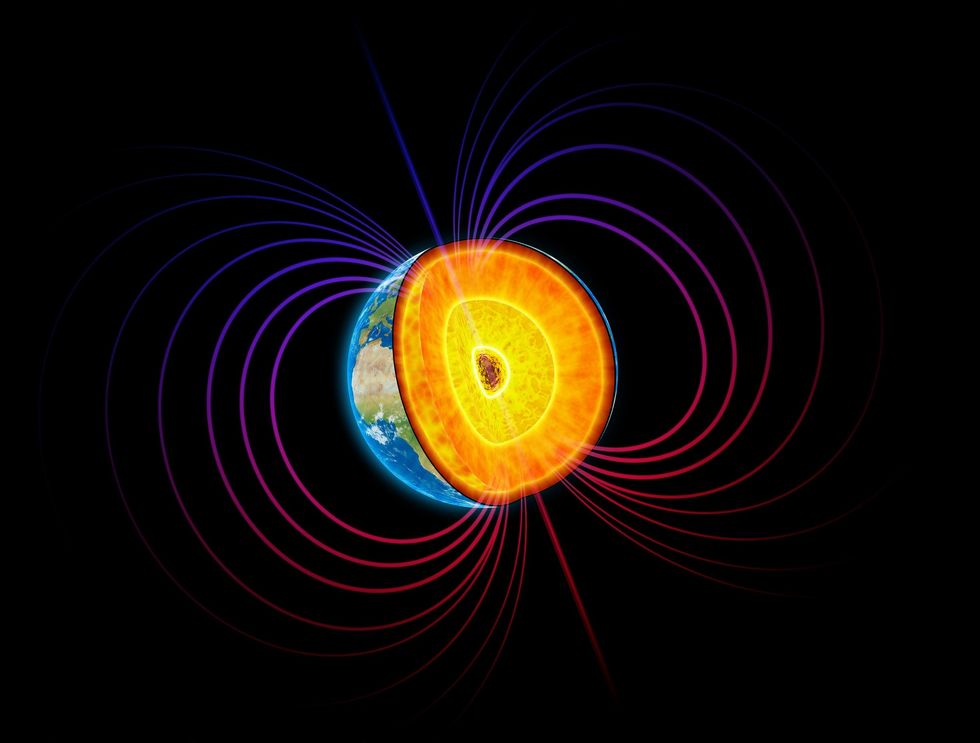

Two enormous and enigmatic masses of hot rock near the planet's core may play a crucial role in generating the Earth's magnetic field, new research suggests.

For several decades, scientists have been aware of these continent-sized formations - one located below Africa and the other beneath the Pacific Ocean.

The structures stretch approximately 1,000 kilometres upwards from the outer core into the overlying rocky mantle.

Their existence has been identified because seismic waves move through them at reduced speeds compared to the surrounding material.

TRENDING

Stories

Videos

Your Say

However, their extreme depth makes precise measurement challenging, preventing researchers from determining their exact composition and characteristics.

These peculiar blobs also appear to have caused the magnetic field to exhibit asymmetrical behaviour that has persisted for millions of years.

Andrew Biggin and his colleagues at the University of Liverpool sought answers by examining the Earth's magnetic field, which has been created over billions of years through the movement of molten iron churning within the core.

The field projects tens of thousands of kilometres into space, shielding the planet from solar wind and cosmic radiation.

Two enormous masses of hot rock near the planet's core are thought to play a crucial role in generating the Earth's magnetic field

|GETTY

Heat moving from the core to cooler surrounding areas determines the precise configuration and characteristics of this magnetic field.

Biggin's research team hypothesised that examining historical changes in the magnetic field could reveal patterns in how heat has travelled through the Earth's core over time.

The scientists gathered data from ancient volcanic rocks, which had preserved the orientation of the magnetic field at various intervals spanning the past tens or hundreds of millions of years.

This collection of records enabled them to construct a comprehensive picture of how the magnetic field had evolved through geological time.

LATEST SCIENCE NEWS:

The team conducted computational modelling to simulate magnetic field generation through heat transfer within the planet's core and mantle, testing configurations both including and excluding the massive rock formations.

When they compared these models against actual magnetic field measurements, the simulations incorporating the blobs provided the closest match to the ancient data.

The research suggests these areas have maintained significantly higher temperatures than their surroundings for hundreds of millions of years, resulting in reduced heat transfer between the core and mantle.

According to the team's modelling, this variation in heat distribution has been vital in both creating and maintaining the Earth's magnetic field.

The investigation also revealed the historical magnetic field displayed asymmetry on average, rather than the bar magnet-like symmetry most geologists had assumed, with persistent systematic deviations over millions of years linked to these formations.

Biggin explained the modelling work could only replicate the key characteristics of the magnetic field under specific conditions.

"These simulations of the convection that's happening in the core, that's generating the magnetic field, can reproduce some of the salient features of the [magnetic] field, but only when you impose this strong heterogeneity in the amount of heat that's flowing out of the top of the core," he said.

Should the findings prove accurate, Biggin noted the temperature variations present in these formations might also be detectable at certain locations in the Earth's uppermost outer core through seismic wave analysis.

However, Sanne Cottaar at the University of Cambridge expressed reservations about this possibility.

"I have my doubts," she said. "It's very challenging for us to map variations within the core, given we have to look through so much mantle material before we see it."