Archaeology breakthrough reveals how wealth inequality over the past 10,000 years was encouraged

The research challenges long-held assumptions that past societies were predominantly egalitarian

Don't Miss

Most Read

Archaeological research has revealed how wealth inequality over the past 10,000 years was encouraged by land-hungry farming practices.

A groundbreaking study led by Professor Amy Bogaard from Oxford University's School of Archaeology shows that where land became scarce, wealth inequality often grew among households.

Conversely, in areas where land remained abundant, wealth was more equally distributed.

The research challenges long-held assumptions that past societies were predominantly egalitarian.

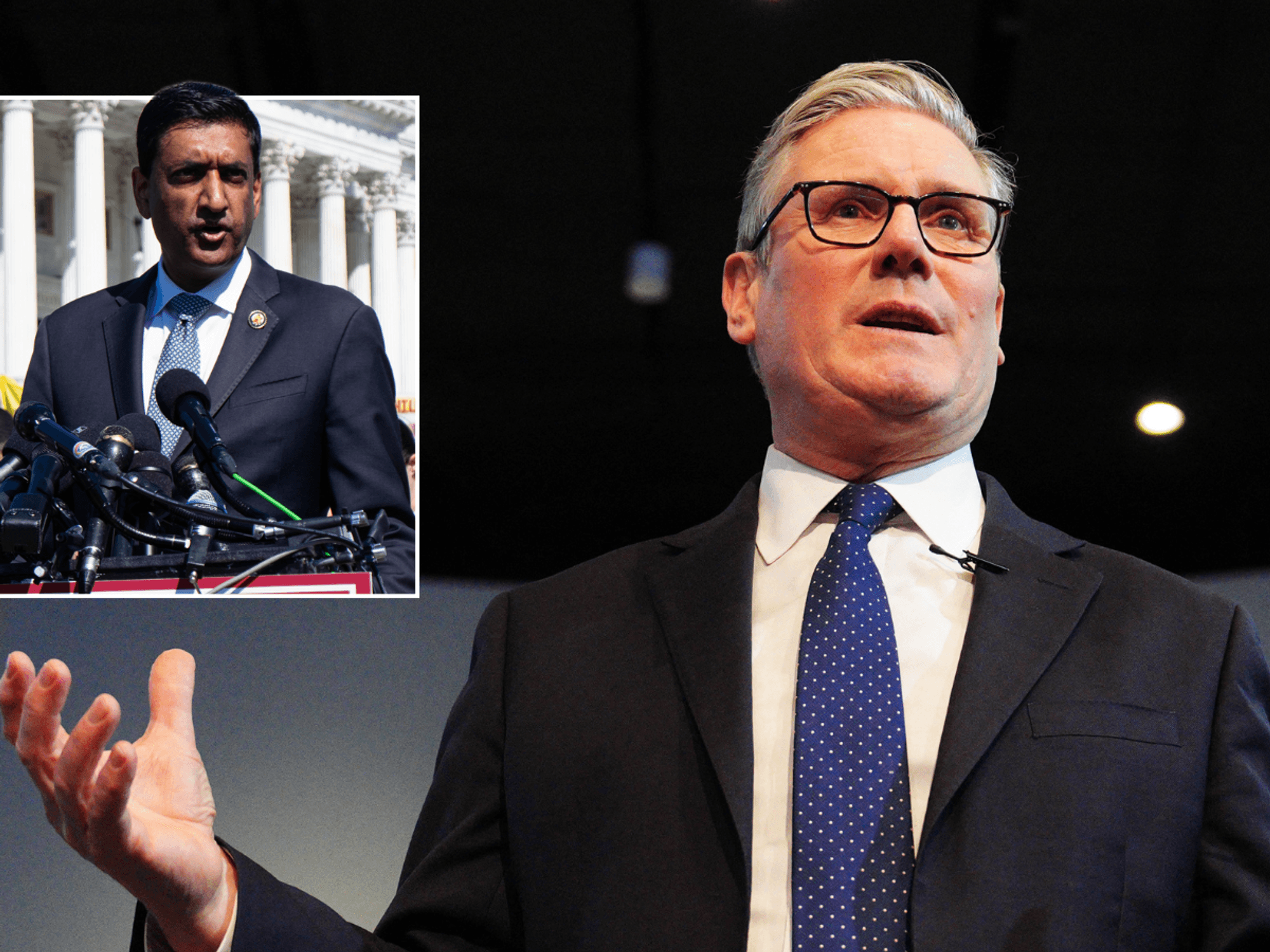

The study involved 27 scientists from around the world who analysed approximately 47,000 houses from more than 1,700 archaeological settlements

|Getty

Instead, it demonstrates how high wealth inequality could become entrenched under specific ecological and political conditions.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was co-edited by Bogaard and Tim Kohler from Washington State University.

It involved 27 scientists from around the world who analysed approximately 47,000 houses from more than 1,700 archaeological settlements.

This extensive research has now been launched as an open-access resource available to the public.

The team, including Oxford archaeologists Shadreck Chirikure and Helena Hamerow, examined variations in house sizes and storage capacities within settlements.

MORE ARCHAEOLOGY BREAKTHROUGHS:

They also investigated how land use and farming practices impacted these variations.

The researchers found that in regions with land-intensive farming systems, particularly those using animal traction for ploughing, high wealth inequality became persistent.

A small number of households would control productive land, creating economic disparities.

In other regions, land became highly valued through terracing, irrigation or drainage systems.

While these engineering projects often began as cooperative endeavours, they frequently resulted in a minority of households gaining control of these landscapes.

The study shows how high wealth inequality emerged across diverse world regions when land came under pressure.

Local population growth and technological investments made land more valuable, fuelling competition.

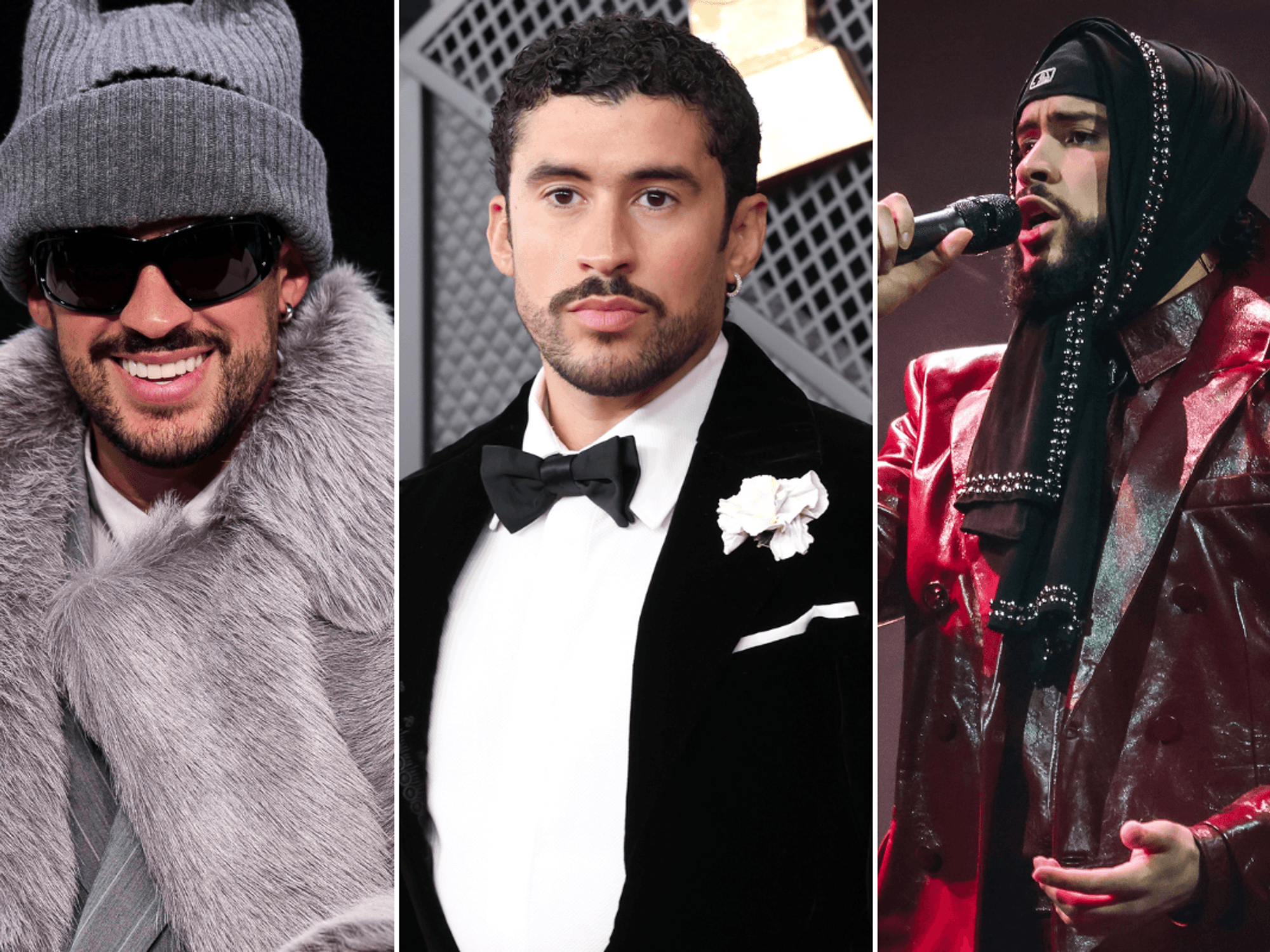

A groundbreaking study led by Professor Amy Bogaard from Oxford University's School of Archaeology shows that where land became scarce, wealth inequality often grew among households

| GettyOver time, larger settlements developed as hubs of wider hierarchies, sustained through land-intensive farming systems.

Professor Bogaard said: "The emergence of high wealth inequality wasn't an inevitable result of farming.

"It also wasn't a simple function of either environmental or institutional conditions."

"It emerged where land became a scarce resource that could be monopolised," she also explained.

Some ancient societies practising land-intensive farming avoided extreme inequality through governance.

Examples include Teotihuacan in Mexico and Mohenjo-daro in the Indus River Basin.

"High wealth inequality has been a challenge for thousands of years," Bogaard noted.

She emphasised that understanding historical patterns enables us to recognise how land-use systems promoted competition.

"The past offers us lessons to navigate these pressing issues today," Bogaard concluded. "The good news is that societies can and have resisted the extremes of high inequality through governance."