Viruses sent into space can still infect bacteria but evolve differently than on Earth

The findings could help improve therapies against drug-resistant infections

Don't Miss

Most Read

Latest

Researchers have discovered viruses transported to the International Space Station evolve differently than on Earth in a remarkable biological breakthrough.

According to research published in PLOS Biology, viruses have retained their ability to infect host cells in bacteria.

The study, led by Phil Huss from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and colleagues, examined how phages—viruses that target bacteria—interact with their microbial hosts under near-weightless conditions.

Findings published on January 13 revealed that whilst infection remained possible in microgravity, the dynamics between viruses and bacteria shifted considerably compared to observations made on Earth.

Both organisms followed distinct evolutionary paths in space, with genetic changes emerging that altered viral attachment mechanisms and bacterial defensive responses.

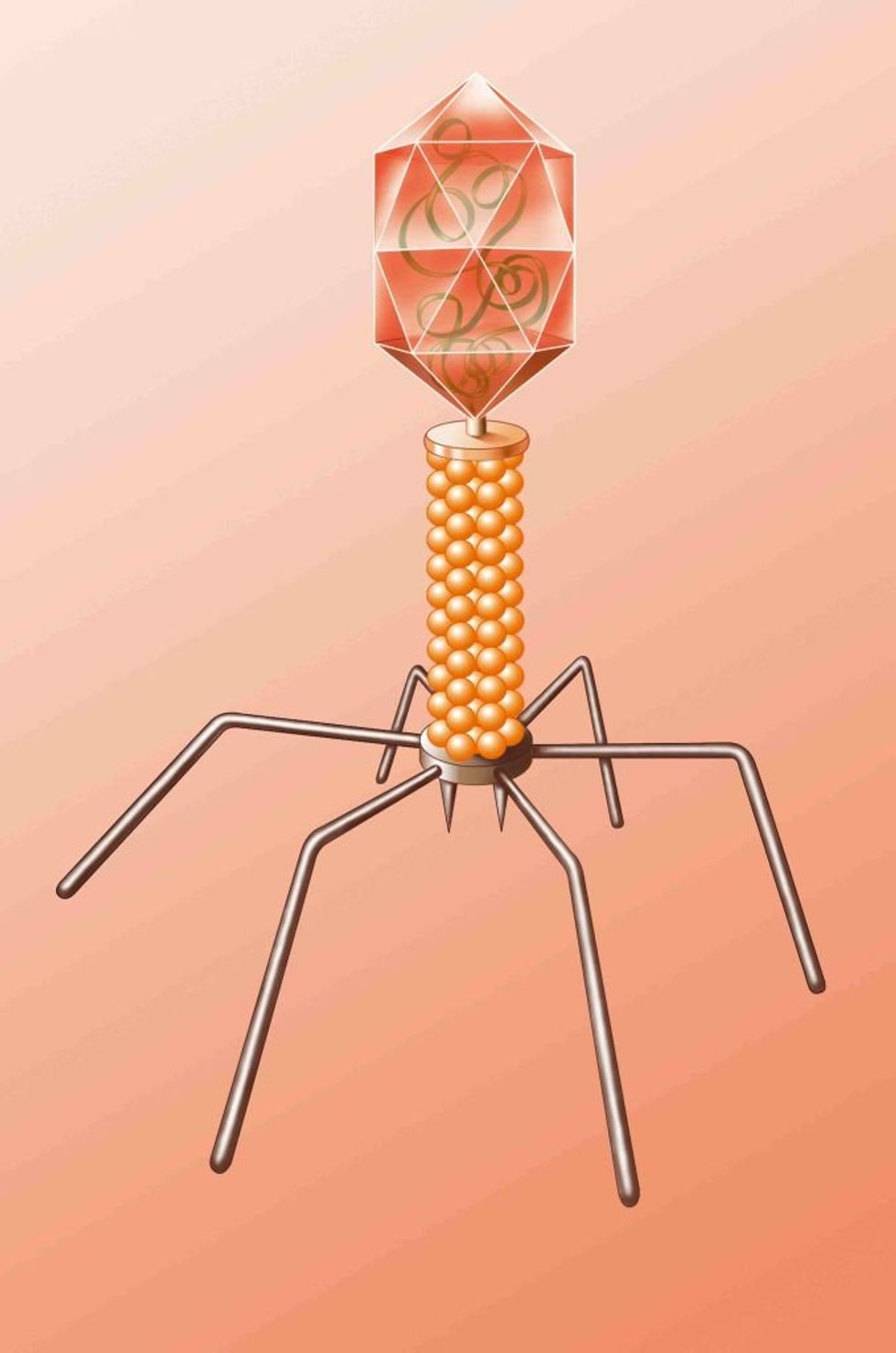

Scientists have long characterised the relationship between phages and bacteria as an evolutionary "arms race".

Bacteria develop protective mechanisms against viral invaders, whilst phages simultaneously evolve strategies to overcome these defences.

Although this interplay has been extensively investigated under normal gravity, the microgravity environment alters both bacterial physiology and the physical dynamics of how viruses collide with their targets.

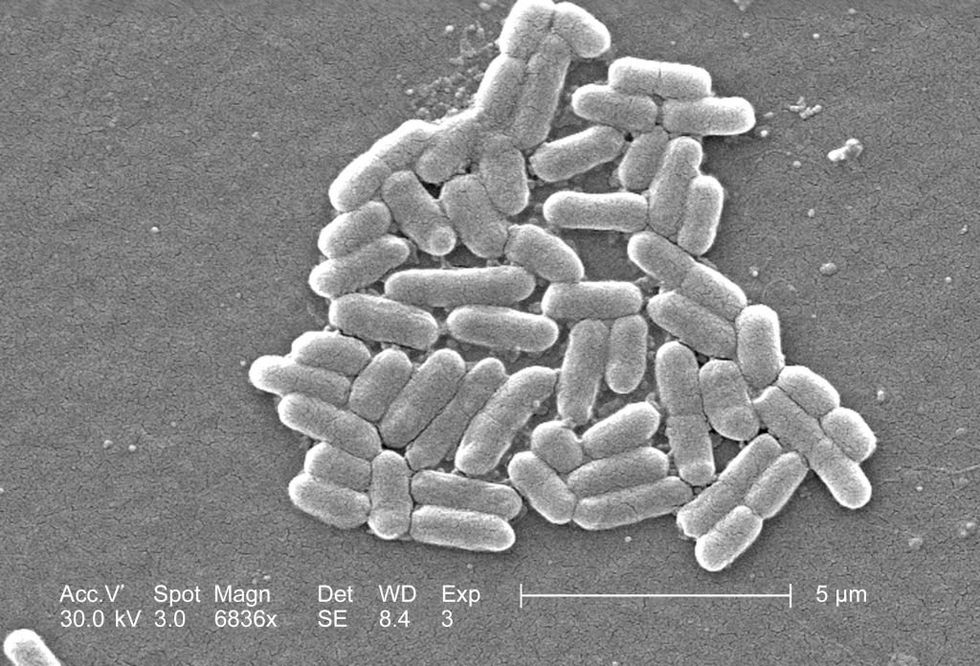

Scientists observed the E Coli micro-organism

|GETTY

To investigate these differences, the research team conducted parallel experiments using E. coli samples infected with a virus called T7.

One set of samples was incubated on Earth, while an identical set was sent to the space station, enabling direct comparison between the two environments.

Examination of the space station samples demonstrated that T7 phages successfully infected the E. coli following an initial delay.

Whole-genome sequencing subsequently uncovered substantial differences in genetic mutations between organisms incubated in orbit versus those on Earth.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS:

The experiment took place on the International Space Station (file pic)

|GETTY

The viruses aboard the ISS progressively developed specific mutations that appeared to enhance their infectious capability and their capacity to attach to bacterial cell receptors.

Conversely, the bacteria in microgravity accumulated genetic alterations that could bolster their defences against viral attack whilst simultaneously improving their survival prospects in weightless conditions.

Researchers employed deep mutational scanning to scrutinise modifications in the T7 receptor binding protein, a crucial component in the infection process.

In turn, this revealed further marked distinctions between space and terrestrial samples.

An example of a Bacterium Phage (file pic)

|GETTY

Follow-up experiments conducted on Earth connected these space-induced changes in the receptor binding protein to heightened effectiveness against E.coli strains responsible for urinary tract infections in humans.

This is bacteria that typically resist T7 infection.

The authors stated: "Space fundamentally changes how phages and bacteria interact: infection is slowed, and both organisms evolve along a different trajectory than they do on Earth.

"By studying those space-driven adaptations, we identified new biological insights that allowed us to engineer phages with far superior activity against drug-resistant pathogens back on Earth."