Californian city rocked by hundreds of earthquakes as locals fear ‘Big One’ imminent

There is an estimated 72 per cent chance of a major, millions-impacting earthquake striking the area in the coming years

Don't Miss

Most Read

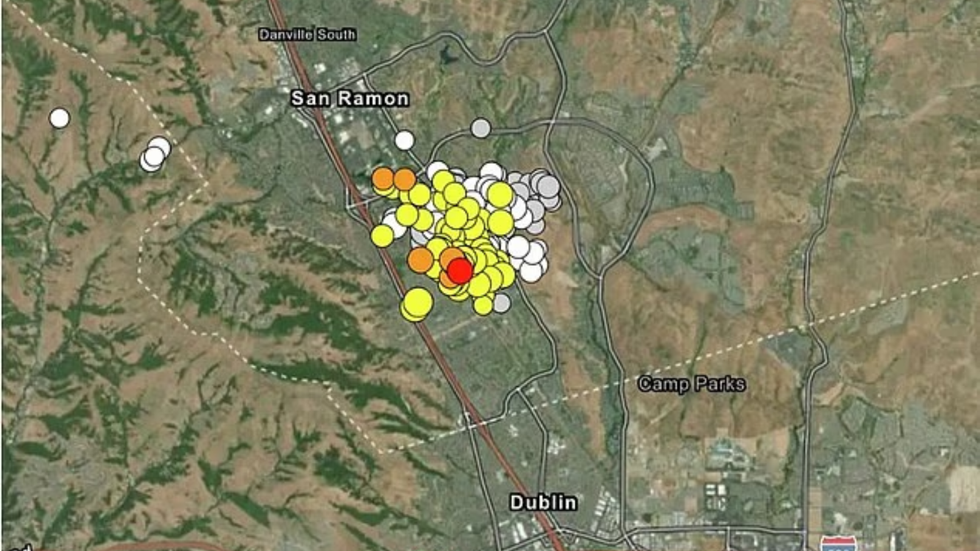

Residents of San Ramon in California's East Bay have experienced more than 300 earthquakes over the past month, prompting widespread concern that a devastating seismic event may be approaching.

The tremors, which began on November 9 with a magnitude 3.8 quake, have continued unabated, with the most recent registering 2.7 magnitude.

San Ramon sits directly above the Calaveras Fault, an active component of the broader San Andreas Fault system.

This fault has the potential to generate a magnitude 6.7 earthquake, which would affect millions across the San Francisco Bay Area.

San Ramon sits directly above the Calaveras Fault, an active component of the broader San Andreas Fault system

|CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS

According to USGS estimates, there is a 72 per cent probability of such an event occurring before 2043.

A quake of this magnitude would constitute a major seismic incident capable of inflicting substantial damage on the densely populated East Bay communities.

Despite the persistent shaking, scientists from the US Geological Survey have sought to calm fears about an imminent large-scale earthquake.

Sarah Minson, a research geophysicist at the USGS's Earthquake Science Center, told SFGATE: "This is a lot of shaking for the people in the San Ramon area to deal with.

"It's quite understandable that this can be incredibly scary and emotionally impactful, even if it's not likely to be physically damaging."

More than 300 earthquakes have shaken San Ramon over the past month

|US GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

She emphasised that the current activity does not point to danger on the region's major fault lines.

"Given the magnitude and locations of the earthquakes that have happened so far, there is no significant risk of something happening on one of the major faults," Ms Minson explained.

Fellow USGS geophysicist Annemarie Baltay echoed this assessment, telling Patch: "These small events, as all small events are, are not indicative of an impending large earthquake."

Ms Baltay nevertheless urged continued vigilance, stating: "However, we live in earthquake country, so we should always be prepared for a large event."

Scientists attribute these earthquake clusters to underground fluids such as water or gas moving through fractures in rock, which weakens surrounding material and triggers rapid successions of minor tremors.

SCIENCE - READ THE LATEST:

Scientists attribute these earthquake clusters to underground fluids moving through fractures in rock

|GETTY

"It is also possible that these smaller earthquakes pop off as the result of fluid moving up through the earth's crust, which is a normal process, but the many faults in the area may facilitate these micro-movements of fluid and smaller faults," Ms Baltay told Patch.

USGS records reveal that comparable swarms struck the San Ramon area in 1970, 1976, 2002, 2003, 2015 and 2018.

Crucially, none of these previous episodes preceded a major earthquake.

"This has happened many times before here in the past, and there were no big earthquakes that followed," Ms Minson told SFGATE.

Research into the 2015 San Ramon swarm revealed that the subterranean fault network is far more intricate than previously understood, comprising numerous small, closely spaced faults rather than a single dominant structure.

Roland Burgmann, a UC Berkeley seismologist involved in that study, suggested to SFGATE that the current sequence may represent an extended aftershock pattern rather than a typical swarm, given that the initial 3.8 magnitude quake was the strongest.

Ms Minson concurred, noting the subsequent tremors likely stem from that first event.

The fault system's complexity includes the Calaveras Fault terminating nearby, with movement potentially transferring to the Concord-Green Valley Fault eastward.

UC Santa Cruz seismologist Emily Brodsky acknowledged the difficulty in drawing conclusions, telling SFGATE: "Although it's the kind of thing you might expect to happen before a big earthquake, we can't distinguish that from the many, many times that have happened without a big earthquake."

Our Standards: The GB News Editorial Charter