Astronomers uncover truth of solar system's 'largest asteroid' that could become lifeline for space exploration

Scientists traditionally believed that the dwarf planet of Ceres was relatively dry

Don't Miss

Most Read

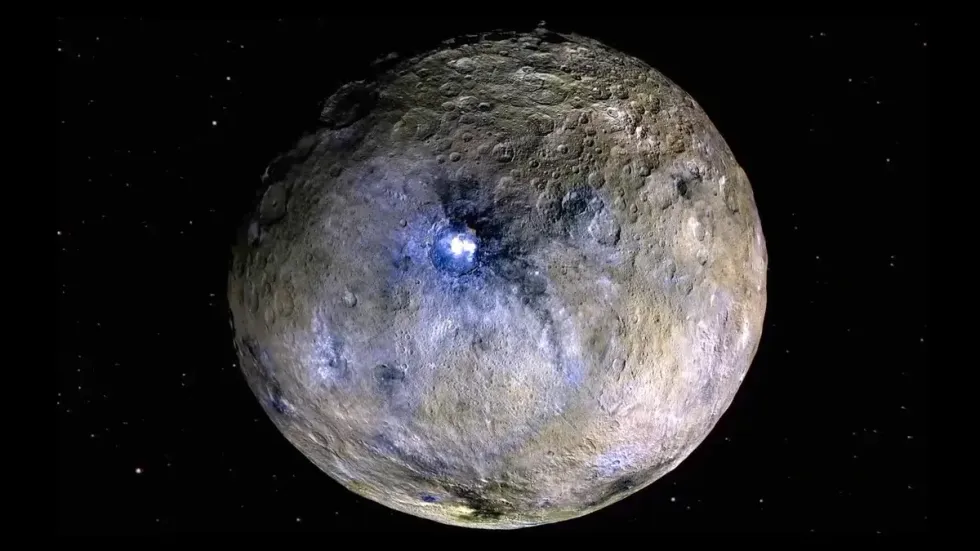

Astronomers have discovered a possible "ancient ocean world" on the largest asteroid in our solar system.

Ceres - which was discovered in 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi - appears to harbour a substantial amount of water ice beneath its surface.

Scientists traditionally believed that the dwarf planet, located in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, was relatively dry.

It was estimated that its ice content was less than 30 per cent - due to its impact craters on its surface, which signalled a lack of significant ice.

Astronomers have discovered a possible 'ancient ocean world' on the largest asteroid in our solar system | NASA / JPL-Caltech / UCLA / MPS / DLR / IDA

Astronomers have discovered a possible 'ancient ocean world' on the largest asteroid in our solar system | NASA / JPL-Caltech / UCLA / MPS / DLR / IDAHowever, new insights into Ceres’ icy surface have now been brought to light by Dr Mike Sori, an assistant professor in Purdue’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences; Ian Pamerleau, a PhD student at Purdue and Jennifer Scully from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL).

"People used to think that if Ceres was very icy, the craters would deform quickly over time, like glaciers flowing on Earth, or like gooey flowing honey," Dr Sori said.

"However, we’ve shown through our simulations that ice can be much stronger in conditions on Ceres than previously predicted if you mix in just a little bit of solid rock."

Their work, using advanced computer simulations, shows how Ceres’ craters have evolved over billions of years.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS:

According to their findings, the surface of Ceres is made up of a "dirty ice crust," which is predominantly ice mixed with rocky material.

This mixture helps the ice stay stable for long durations, maintaining the crater formations that initially led scientists to think Ceres was largely dry.

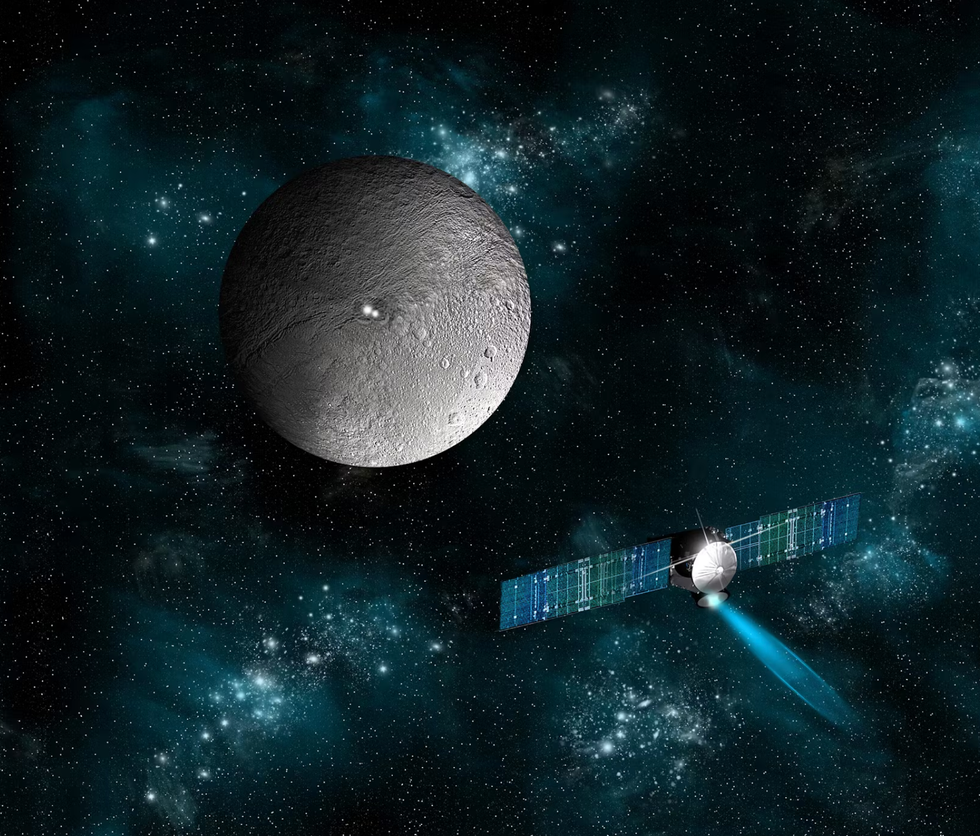

NASA’s Dawn mission, which set off on September 27, 2007, provided crucial data from 2015 to 2018.

Pamerleau said: "We used multiple observations made with Dawn data as motivation for finding an ice-rich crust that resisted crater relaxation on Ceres."

The artist’s illustration shows NASA’s Dawn spacecraft approaching Ceres in 2012

|Getty

The team's simulations incorporated a mechanism in which ice can move when even a small amount of rocky material is mixed in.

This discovery resolves the apparent contradiction between the craters and the high ice content, indicating that Ceres could be an icy world without the surface ice quickly flowing off.

"Ceres really looks more like a planet," Dr Sori added.

"To me, the exciting part of all this, if we’re right, is that we have a frozen ocean world pretty close to Earth."