Archaeology breakthrough as Mayan astronomers predicted solar eclipses for CENTURIES over 1,000 years ago

Researchers suggest the Maya techniques, if maintained today, could still accurately forecast eclipses visible from Mexico

Don't Miss

Most Read

Astonishing new archaeological research has uncovered the mathematical secrets behind the ancient Maya’s ability to predict solar eclipses.

The groundbreaking analysis published in Science Advances has revealed the sophisticated techniques Maya astronomers employed to forecast the celestial phenomena with remarkable accuracy for more than seven hundred years.

Investigators focused their efforts on the renowned eclipse table within the Dresden Codex, a 12th-century Maya text that represents one of the rare surviving pre-Columbian American manuscripts.

This document contains astronomical insights accumulated over generations by Maya scientists, religious leaders and calendar specialists who meticulously observed the movement of the stars.

For years, academics believed the codex's 405-month sequence served solely as an eclipse predictor.

However, researchers John Justeson and Justin Lowry have overturned this long-held assumption.

Their findings demonstrate that the table initially functioned as a lunar calendar before being modified to monitor solar eclipses through coordination with the Maya's 260-day sacred calendar.

This ritual calendar, employed for divination and prophetic purposes, connected astronomical phenomena with religious and community activities.

A new archaeological breakthrough has revealed secrets behind the ancient Maya’s ability to predict solar eclipses

|GETTY

Computer modelling showed the table's 11,960-day span, equivalent to 405 lunar cycles, precisely corresponds to 46 repetitions of the 260-day calendar.

This alignment allowed Maya astronomers to determine when eclipses would occur on specific ceremonial dates, merging empirical observation with spiritual importance.

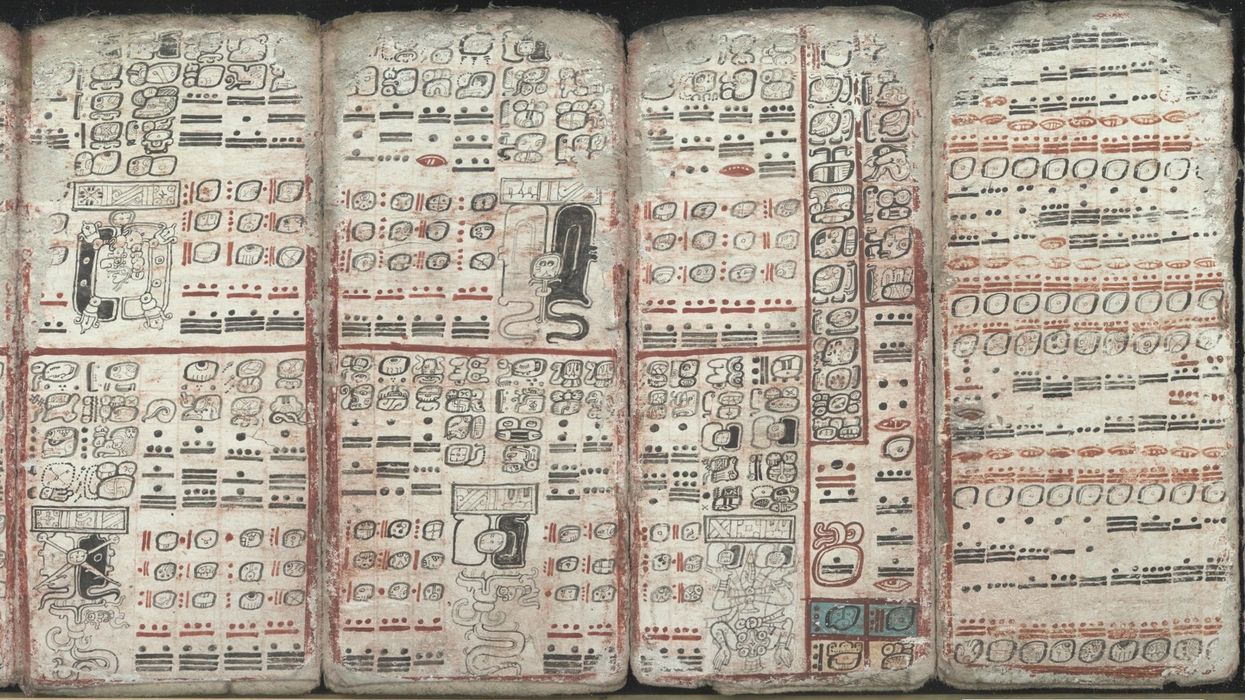

The table's eight pages contain "stations" marking each new moon and times when solar eclipses might occur.

These stations typically appear at six-month intervals, approximately 177 days apart, matching the period required for lunar realignment with Earth and Sun.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS

Researchers examined the Dresden Codex, a 12th-century Maya text that represents one of the rare surviving pre-Columbian American manuscripts

|GETTY

Previous scholarship suggested the Maya simply restarted their table upon completion, but the research uncovered a more sophisticated approach.

They employed overlapping sequences, resetting calculations at either 223 or 358 lunar-month intervals, which correspond to contemporary saros and inex eclipse patterns.

These strategic resets eliminated small errors that accumulated gradually, maintaining predictive accuracy throughout the entire period from 350 to 1150 CE.

By implementing four 358-month resets for each 223-month adjustment, Maya astronomers successfully aligned their predictions with every visible solar eclipse in their territory across eight centuries.

Researchers suggest the Maya techniques, if maintained today, could still accurately forecast eclipses visible from Mexico

|GETTY

Modern comparison of Dresden Codex data with historical eclipse records confirms this exceptional precision.

For the Maya, eclipses represented divine communications—moments when supernatural forces consumed sunlight, indicating celestial displeasure or transformation.

Nevertheless, these religious interpretations rested upon rigorous mathematical foundations and systematic observation comparable to ancient Babylonian or Greek astronomy.

The researchers determined that this methodology, if maintained today, could still accurately forecast eclipses visible from Mexico, years before the first telescopes were developed in 1608.

Our Standards: The GB News Editorial Charter