Alex Phillips: We need to talk about cultural appropriation

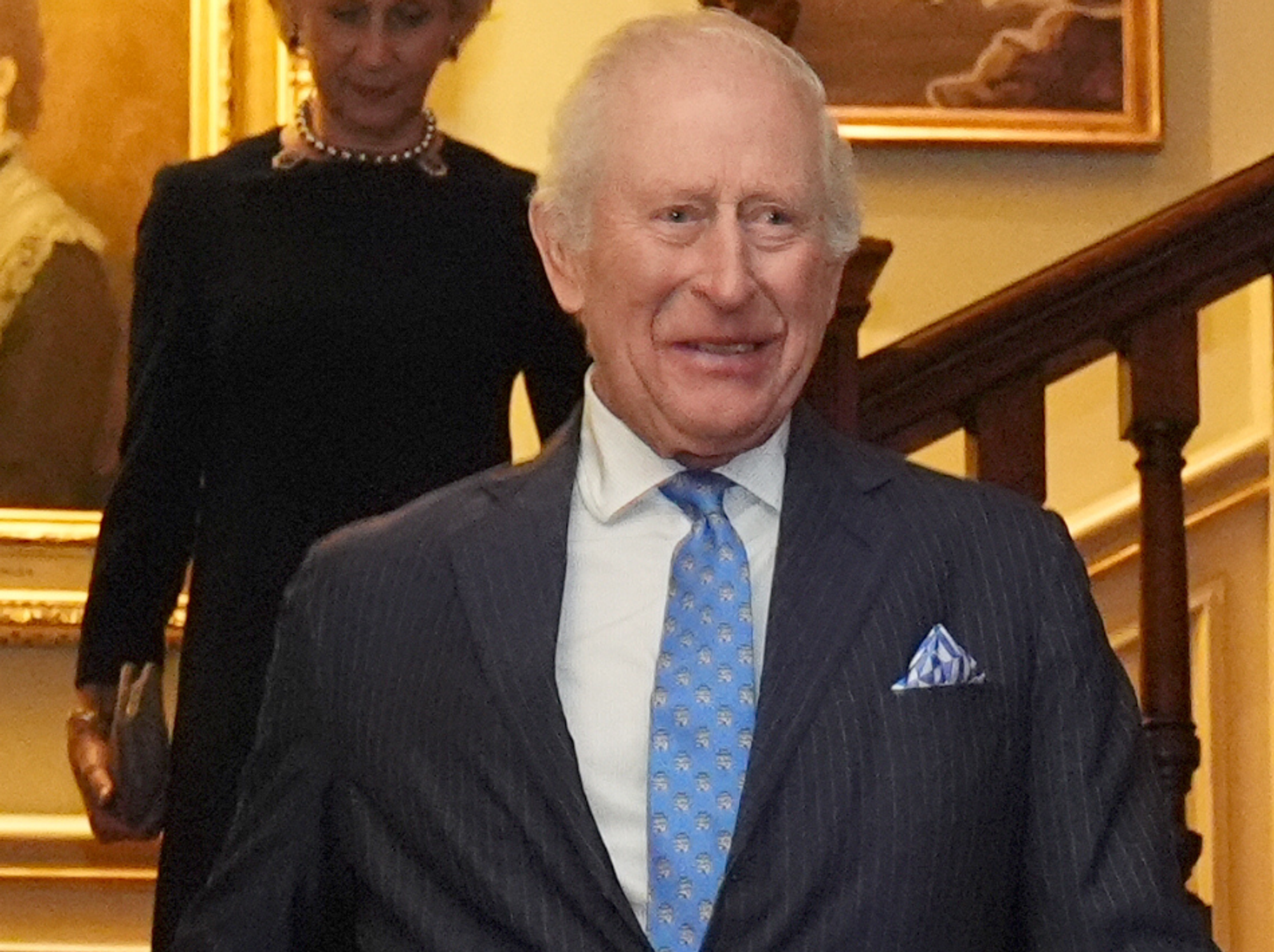

By Alex Phillips

Published: 02/12/2021

- 16:13Updated: 02/12/2021

- 21:58How has celebration become something that other people can term an insult?

Don't Miss

Most Read

Today’s world is an offense minefield. Just as soon as we wrap our heads around one taboo, another crops up, with the rules around probity and socially acceptable normatives rewritten by the hour by anybody, it seems, with a TikTok account. And Cultural Appropriation is one of the topics that regularly instigates a social media storm. The fury over the Pepsi advert where Kendall Jenner appeared to be leading a BLM protest, or the recent outrage over Jesy Nelson, former member of Little Mix, who was accused of mimicking black fashion in her latest music video. Then there are more peculiar examples, such as the case of two academics accused of pretending to be from minority backgrounds when their origins are exclusively Caucasian.

So when is adopting elements of a different culture appreciating it? And when is it appropriating it? And what does that even mean?

It’s plain to see that there is little orthodoxy around the notion of appropriation with many and various subjective interpretations as to what is deemed offensive and what is not. Yet for those who are vocal on the matter, the common denominator is the position that when someone from a dominant culture adopts fashions, vernacular or artistic elements from a culture that has been oppressed or marginalised it is insensitive at best, or outright offensive at worst.

So where does that leave us all? Is it, say, offensive if a black recording artist utilised Asian fashions, symbols, traditions and styles? Or for a Caucasian to wear their hair in cornrows on the beach in Barbados? What about when black culture imitates the ideals of white beauty? And who can stake a claim in what actually belongs to which culture?

As someone who has lived around the world, from India to China to Ghana to Kenya to the Maghreb, my house, and my wardrobe, is full of accessories, clothing and decor I have collected along the way, having contributed to the economies of some of the poorest communities in those countries by purchasing crafts made by their artisans. Yet where I once wore my Masaai beaded choker with pride, I would now have to think twice whether people would deem this somehow offensive. When people visit my cottage and see a sitting room styled with a range of upholstery from the souks of Morocco, is that, too, something I should be ashamed of? If I lay the table for a dinner party of a cuisine I have adopted from one of the many countries I have lived in, is it wrong to lay the table with chopsticks, or serve a thali on a banana leaf? Am I allowed to dance to highlife music, burn incense and light diyas, use foreign slang and French African expressions I have learned during my travels, or must I, as a white woman, always stay in my lane?

How has celebration become something that other people can term an insult?

Today, we really need to talk about cultural appropriation.