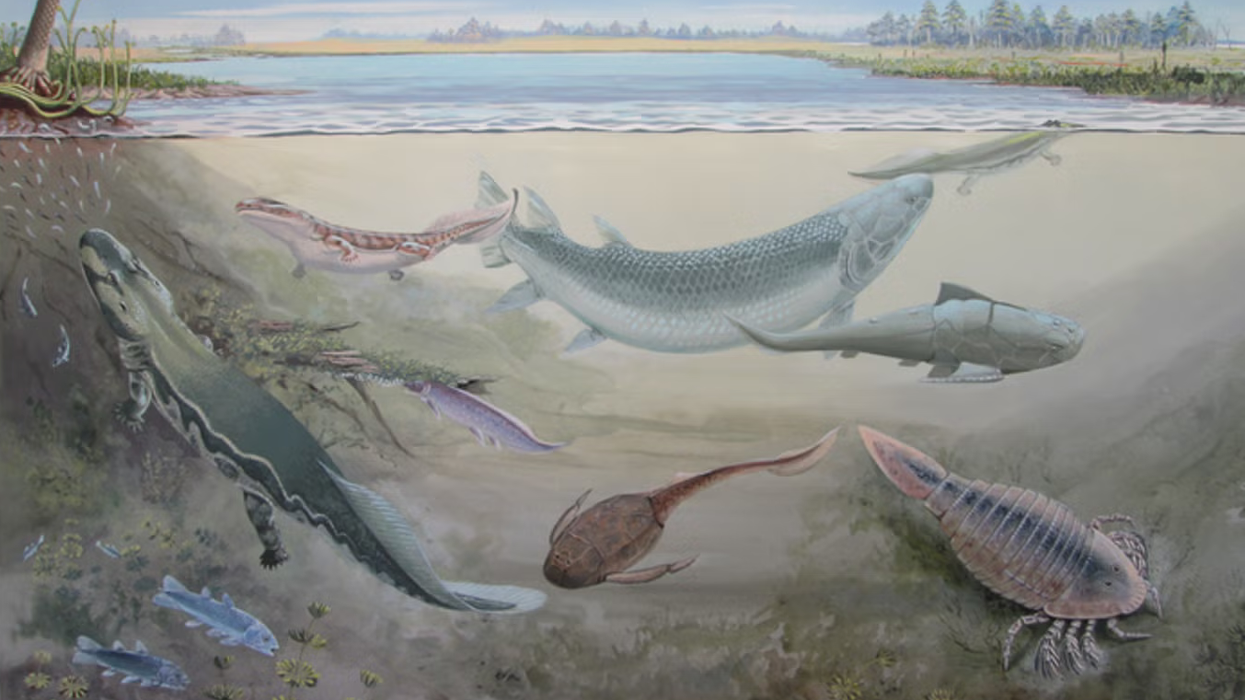

New study of prehistoric fish could rewrite our understanding of evolution

Placoderms are understood to be the first vertebrates with teeth

|PLOS ONE

Australian researchers found the extinct fish developed the ability millions of years earlier than previously thought

Don't Miss

Most Read

Ancient armoured fish possessed sophisticated tooth replacement mechanisms more than 380 million years ago, Australian researchers have discovered using advanced imaging technology.

The breakthrough finding reveals that placoderms, prehistoric predators with bony plates covering their heads and bodies, could break down and replace teeth through a process called resorption.

Australian scientists employed synchrotron X-ray imaging to examine fossils from Western Australia's Gogo Formation, an ancient tropical reef system.

Their research, published in the Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, demonstrates that these extinct fish developed the ability to shed teeth millions of years earlier than previously thought.

The discovery challenges long-held assumptions about placoderm biology and their evolutionary relationship to modern vertebrates.

The Gogo Formation on Gooniyandi Country preserves remains of numerous placoderm species that inhabited the Devonian reef ecosystem between 359 and 438 million years ago.

These armoured fish dominated Earth's oceans for over 80 million years, displaying remarkable diversity in their feeding strategies and dental structures.

Researchers studied multiple specimens, including Eastmanosteus, a two-metre apex predator with blade-like teeth and prominent fangs, and Compagopiscis, a smaller species that consumed arthropod prey using sharp, pointed teeth.

Humans are not the only animals that can shed teeth

|GETTY

The team's investigation centred on Bullerichthys, which possessed flat teeth arranged around a bony plate, perfectly adapted for crushing hard-shelled organisms.

This species provided crucial evidence for understanding how tooth replacement evolved in vertebrates.

The research team discovered that Bullerichthys specimens of varying sizes possessed different numbers of tooth rows, indicating developmental changes throughout the fish's lifetime.

At the Australian Synchrotron ANSTO Research Facility in Melbourne, high-resolution imaging revealed that older teeth underwent internal resorption, with spongy bone gradually replacing the central dentine tissue.

Sharks can also shed teeth

|UNSPLASH

Crucially, the tooth plates displayed pits with distinctive scalloped edges, evidence of osteoclast cells actively breaking down bone material.

These specialised cells, which enable tooth loosening and replacement in modern animals, were distributed across the entire tooth plate surface rather than confined to individual teeth.

The extent of resorption varied between life stages, with juvenile specimens showing significantly more activity than adults.

Beneath each tooth row, scientists identified shallow pits containing newly formed teeth, suggesting the presence of dental lamina tissue comparable to that found in modern bony fish like trout.

This sophisticated replacement system indicates that placoderms shared more evolutionary traits with contemporary vertebrates than researchers previously recognised.

The findings demonstrate that tooth resorption, essential for dental replacement in mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish today, originated at least 380 million years ago.

The research provides fresh insights into vertebrate evolution, revealing that these ancient armoured fish developed complex biological mechanisms far earlier than scientists had assumed.

The discovery adds another crucial element to understanding the evolutionary journey from prehistoric marine predators to modern vertebrates.