Easter Island mystery solved as scientists find clues behind 'extinction event'

One potential last piece of the puzzle had gone under the radar for centuries - but scientists believe they have found it

Don't Miss

Most Read

A dark Easter Island mystery has been solved after scientists found clues as to what caused an "extinction event" on the island.

A new study has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science looking into why all the treets on Rapa Nui disappeared - and has discovered an unlikely culprit.

Records show that the island at one point supported an huge palm forest which housed between 15 to 19 million Paschalococos disperta trees.

But between the years 1200 and 1650 AD the vegetation on Rapa Nui was replaced by grass and shrubs.

TRENDING

Stories

Videos

Your Say

Dr Terry Hunt, of the the University of Arizona, and the University of Birmingham's Dr Carl Lipo said in their study that one factor had gone under the radar in the deforestation: rats, and their "seed predation".

Seed predation is where animals like rats turn to seeds and grains as a food source, leaving them damaged and unable to grow.

Using ecological modelling, the study showed that a single breeding pair of Polynesian rats could grow to a population of around 11.2 million in just 42 years.

The rats then went on to eat 95 per cent of the palm seeds were eaten, preventing the trees from growing back.

Polynesian rats have now been linked with the deforestation of Rapa Nui

|WIKIMEDIACOMMONS

The palms were particularly vulnerable because they produced a few, large, nutrient-rich seeds - the ideal food source for rodents.

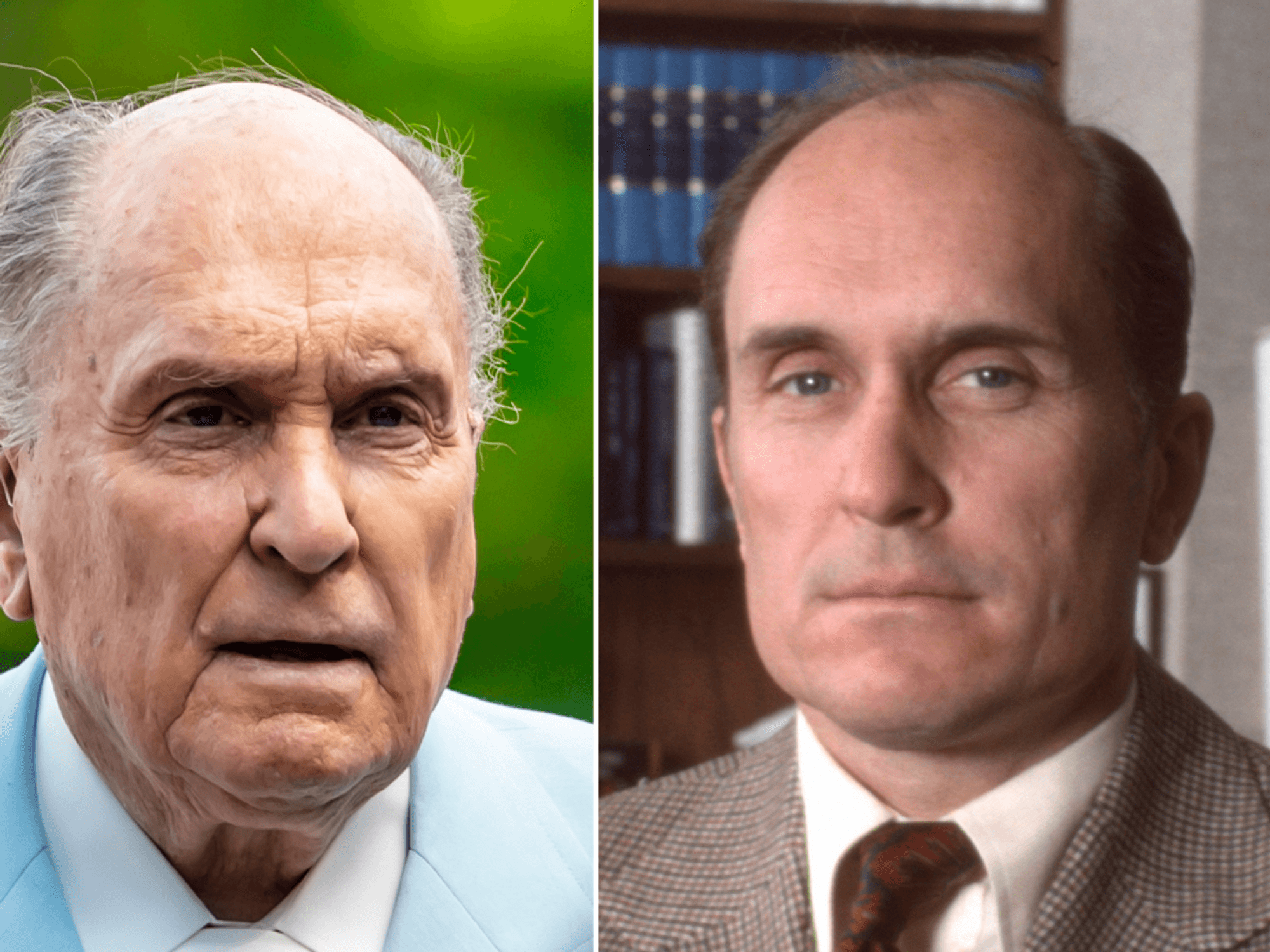

The island has previously been used as a cautionary tale about human "ecocide".

But this new discovery has changed this thought and shifted the blame onto the invasive rats.

Other evidence to support this new theory came from other Pacific islands onto which the rats were never introduced.

EASTER ISLAND DISCOVERIES - READ MORE:

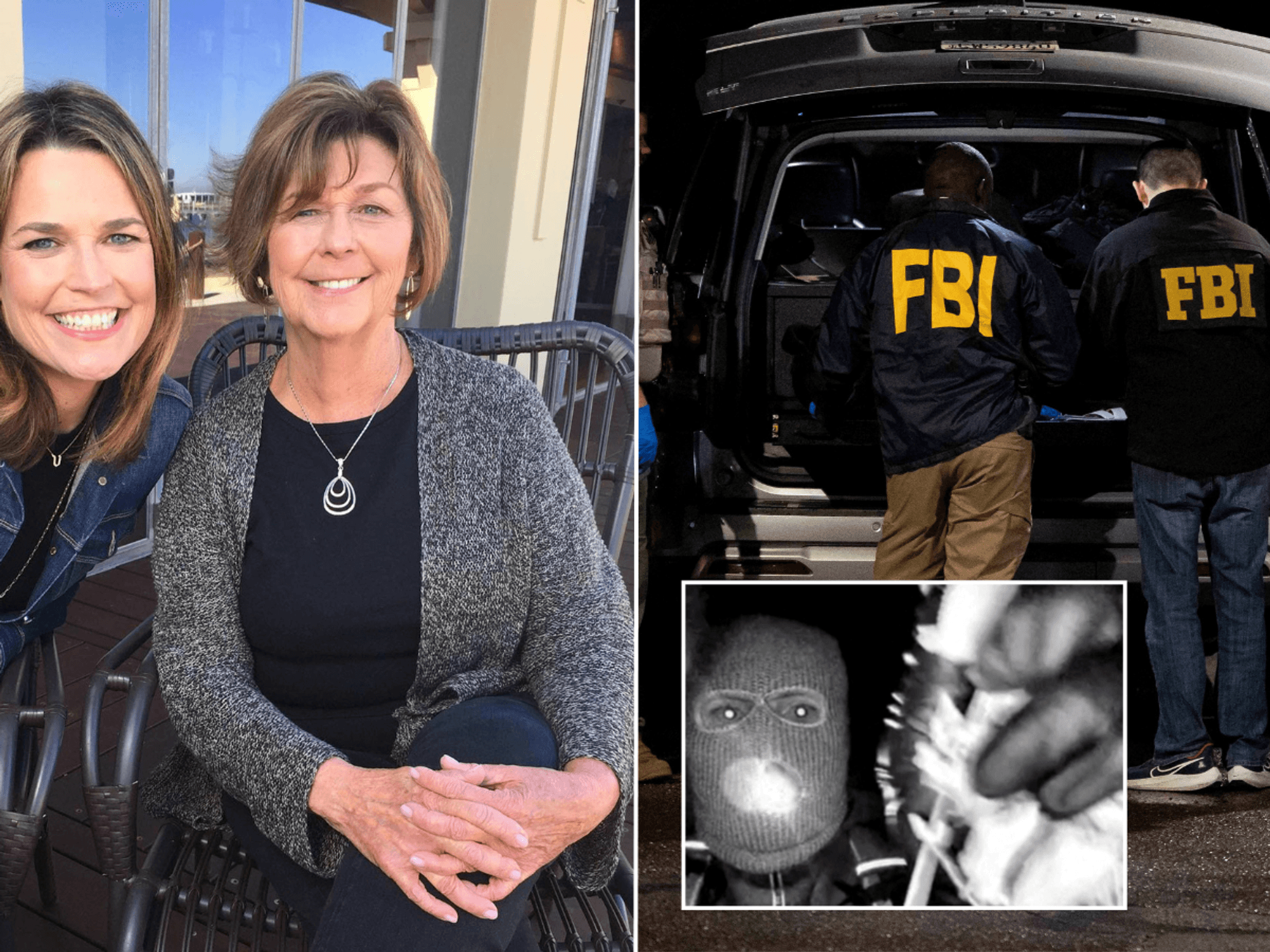

PICTURED: Easter Island's Anakena Beach, where the research took place

|GETTY

In such cases, the native palms persisted despite humans living nearby.

In comparison, on islands where the rats did arrive, palm populations declined significantly before direct human clearing.

Excavations from Anakena, a beach on Rapa Nui, show a boom-bust trajectory of the rat population which aligned with how invasive species tend to operate.

Rodent numbers surged after their arrival on the island, then dropped by around 93 per cent as their food source collapsed.

The island had previously been used as a cautionary tale about man's impact on the environment

|GETTY

This evidence also challenged previous theories which suggested that human hunting reduced rat numbers.

Researchers had previously minimised the impact of rats and instead blamed humans for the island's deforestation, pointing to land clearing, fire and resource overuse as the reasons.

Dr Hunt and Dr Lipo argued that these theories do not consider how biological invasions and human land use would have interacted.

Instead, their evidence of archaeological data, faunal analysis, and ecological modelling showed that rats alone could have eventually caused palm extinction, while human activities quickened the process and shaped its geography.