Archaeologists uncover earliest known use of poison-laced weapons dating back 60,000 years

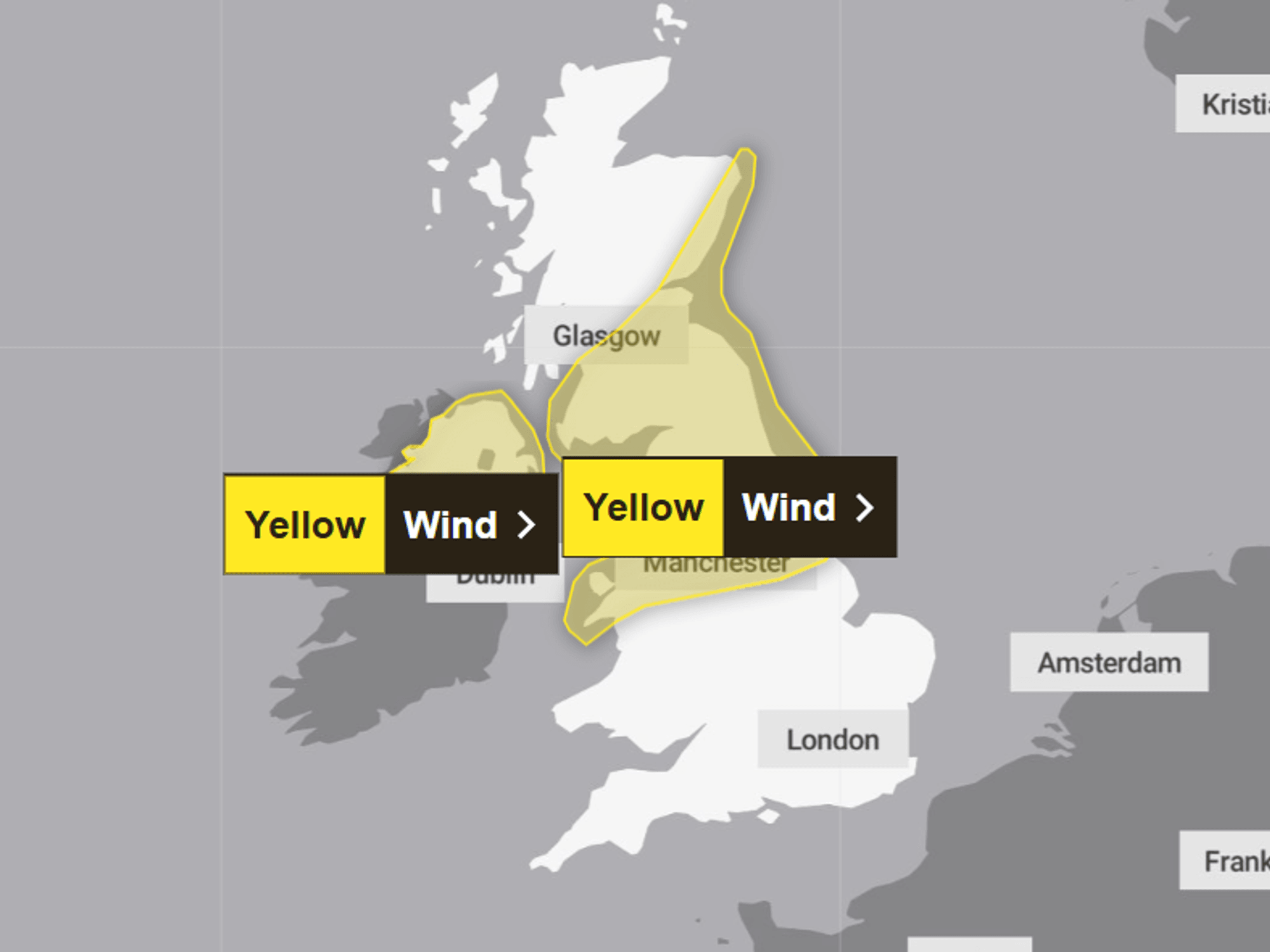

The breakthrough comes from analysis of arrowheads excavated from rock shelter in South Africa

Don't Miss

Most Read

Latest

Archaeologists have uncovered what they believe to be the earliest direct chemical proof ancient humans employed poison on their hunting weapons.

The breakthrough comes from analysis of 60,000-year-old stone arrowheads excavated from Umhlatuzana rock shelter in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

The research, published in Science Advances, pushes back the confirmed use of toxic substances in hunting by tens of thousands of years.

Before this discovery, solid evidence for poisoned hunting implements extended only to approximately 8,000 years ago.

"This is the oldest direct evidence that humans used arrow poison," says archaeologist Marlize Lombard from the University of Johannesburg.

The findings suggest early modern humans in southern Africa possessed far more sophisticated technological capabilities than previously demonstrated through physical evidence.

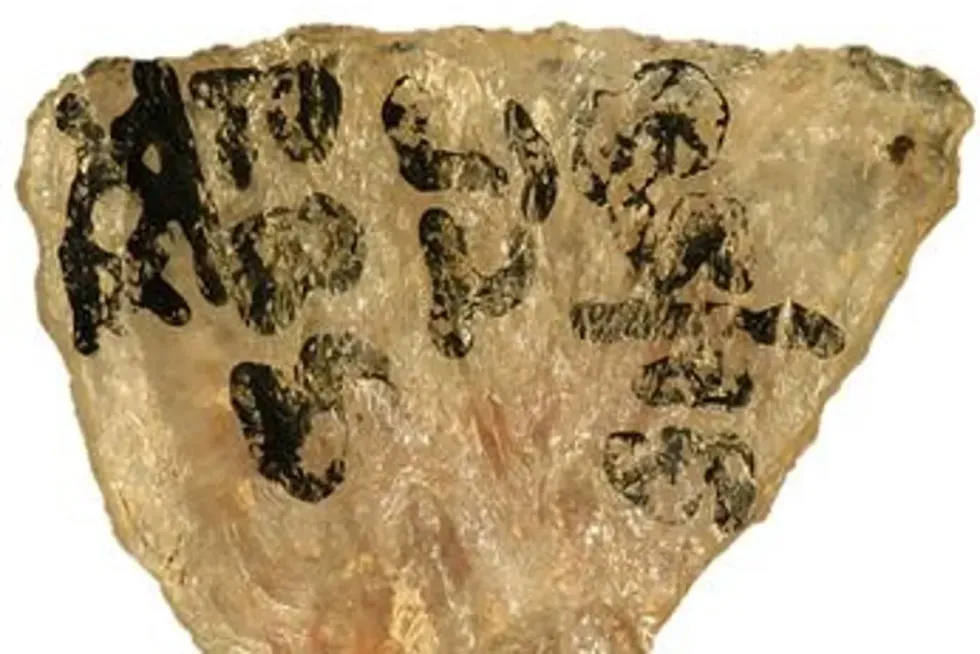

Scientists examined ten small quartzite flakes, each roughly one centimetre across, that had been recovered from the site in 1985. Chemical testing revealed traces of the toxic alkaloids buphandrine and epibuphanisine on five of these ancient tools.

These compounds derive from Boophone disticha, a native plant commonly known as gifbol or poison bulb. The toxin comes from a milky substance secreted by the plant's root bulb.

The breakthrough comes from analysis of stone arrowheads

|SUPPLIED

"If we found it on only one artefact it could have been coincidental," says Prof Lombard. "But finding it on five out of 10 sampled artefacts is extraordinary, suggesting that it was deliberately applied 60,000 years ago."

To verify their results, researchers also tested arrowheads collected by Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg during his visit to South Africa in the 1770s. Those 250-year-old weapons contained the same deadly alkaloids.

The poison proves lethal to rodents within half an hour and can induce nausea, respiratory failure and coma in humans. When used against larger game such as eland, kudu or wildebeest, the toxin may take hours or even days to fully incapacitate the animal.

This slower action meant prehistoric hunters would have needed to track their wounded prey over considerable distances before delivering a final blow.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS

A Botswana bushman with a traditional bow and arrow

|GETTY

Indigenous communities in southern Africa continue to employ the same plant-based poison when hunting springbok and even larger animals, including zebra and giraffes.

Prof Lombard suspects this knowledge has been passed down continuously for at least 60,000 years.

The San people of the region still extract the milky sap from gifbol roots, processing it into a paste that they apply to their arrow tips.

The discovery offers compelling evidence that Stone Age hunters possessed cognitive abilities remarkably similar to modern humans.

Creating poisoned arrows required not merely technical skill but also strategic foresight and an understanding of cause and effect over extended timeframes.

"It shows advanced planning, strategy and causal reasoning — something that is very difficult to demonstrate for people living so long ago, but for which the evidence is increasing every year," says archaeologist Justin Bradfield.

Sven Isaksson from Stockholm University describes the find as early proof of sophisticated plant use, saying: "This is something else — the use of biochemical properties of plants, such as drugs, medicines and poisons."

Anders Högberg, from Sweden's Linnaeus University, added: "Using arrow poison requires planning, patience and an understanding of cause and effect. It is a clear sign of advanced thinking in early humans."

Our Standards: The GB News Editorial Charter