Archaeology breakthrough as early humans hunted and ate giant sloths as well as other Ice Age beasts

Giant sloths reached lengths of six metres and weighed approximately 4,000 kilograms

Don't Miss

Most Read

Latest

Early humans living in South America hunted and ate megafauna such as giant sloths which have since gone extinct, a new study has revealed.

Detailed analysis of archaeological evidence showed that humans considered giant beasts, also including giant armadillos and prehistoric horses, as a regular food source rather than opportunistic prey.

TRENDING

Stories

Videos

Your Say

The new research challenges previous beliefs that such large animals went extinct solely due to climate change, and instead suggests that human hunting did play a role.

The study, published in Science Advances, collated data from 20 different sites dating between 13,000 and 11,600 years ago throughout present-day Argentina, Chile and Uruguay.

At three quarters of the sites, more than 80 per cent of the animal bones present were from species of megafauna which weighed at least 44 kilograms.

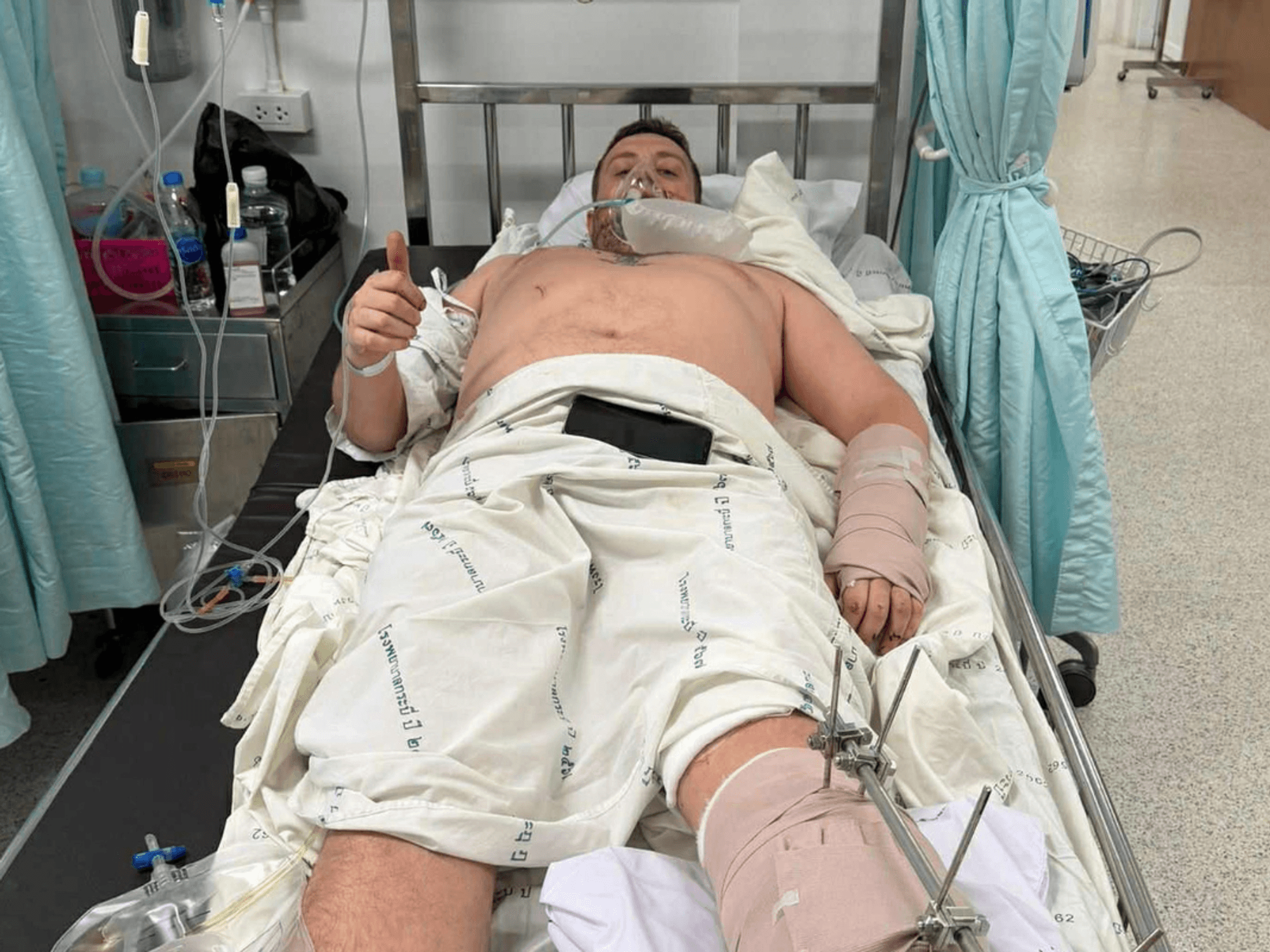

It was previously thought that many of these giant beasts were too large for humans to hunt efficiently, with giant sloths reaching lengths of six metres (20 feet) and weighing approximately 4,000 kilograms (8,800 pounds).

Giant sloths reached lengths of six metres (20 feet) and weighed approximately 4,000 kilograms (8,800 pounds)

|GETTY

Cut marks, fracture patterns and spatial associations in the bones were among the signs looked for by scientists to reflect butchering and human involvement.

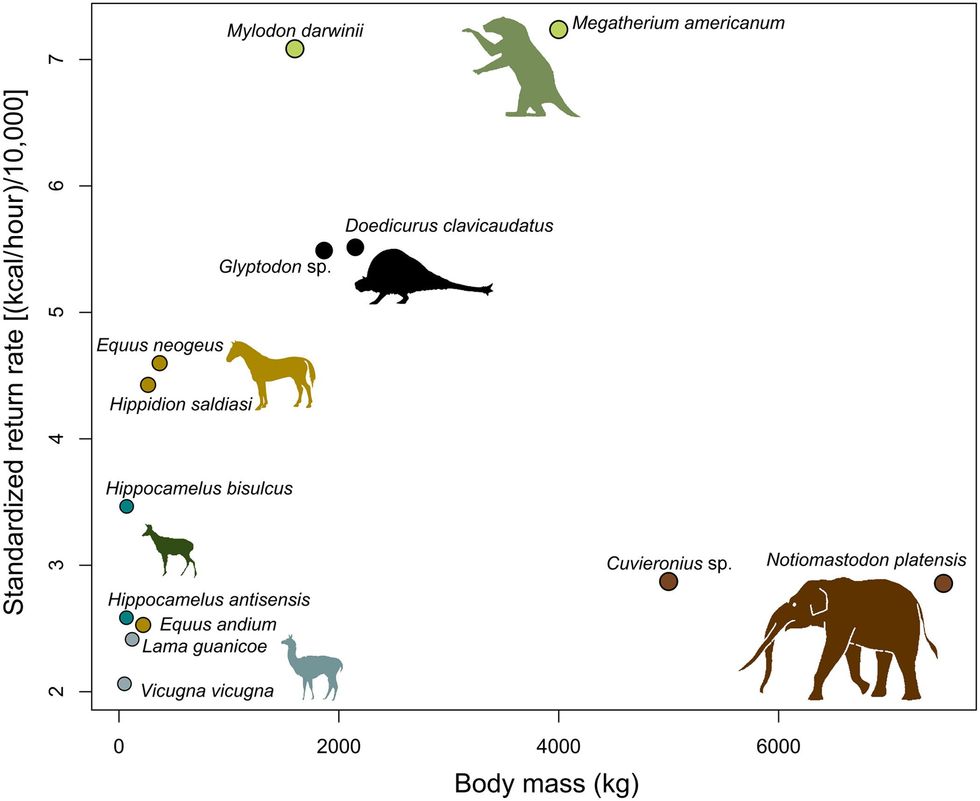

Researchers created a model in order to rank prey which took into account the energetic return of a species relative to the effort required for hunting and processing them.

In every case, megafauna offered higher calorific returns than small mammals.

This suggested that early humans maximised their hunting efforts by focusing on larger animals, making giant sloths and giant armadillos preferred prey.

ANCIENT ANIMALS - READ MORE:

- New dinosaur species is found in Britain as researchers hail 'remarkable' discovery

- New study of prehistoric fish could rewrite our understanding of evolution

- Palaeontology breakthrough as trapped insects give 'little windows' into ancient life on Earth

- New 'apex predator' dinosaur species discovered with crocodile bones still in its mouth

Megafauna offered higher calorific returns than small mammals

|SCIENCE ADVANCES

Scientists believe the new study provided evidence to counter one of the most cited criticisms of the "human overkill" hypothesis.

This stated that early humans tended to favour small animals which were more manageable to hunt and process.

Instead, the research concluded that humans played a large role in late Pleistocene ecological dynamics and it is therefore likely their hunting contributed to the decline and eventual extinction of megafauna.

Around 11,600 years ago, as megafauna species became rarer, humans were forced to expand their diets to include wider ranges of meat, including guanacos, deer and rodents.

Although the study does acknowledge vegetation change, ecosystem dynamics and climate change influenced megafaunal declines, it emphasises the role of human predation, placing it as the primary reason for the Quaternary extinction discussion in South America.