A national reckoning that has been a long time coming is finally upon us - Stuart Fawcett

A national reckoning that has been a long time coming is finally upon us - Stuart Fawcett |

PA

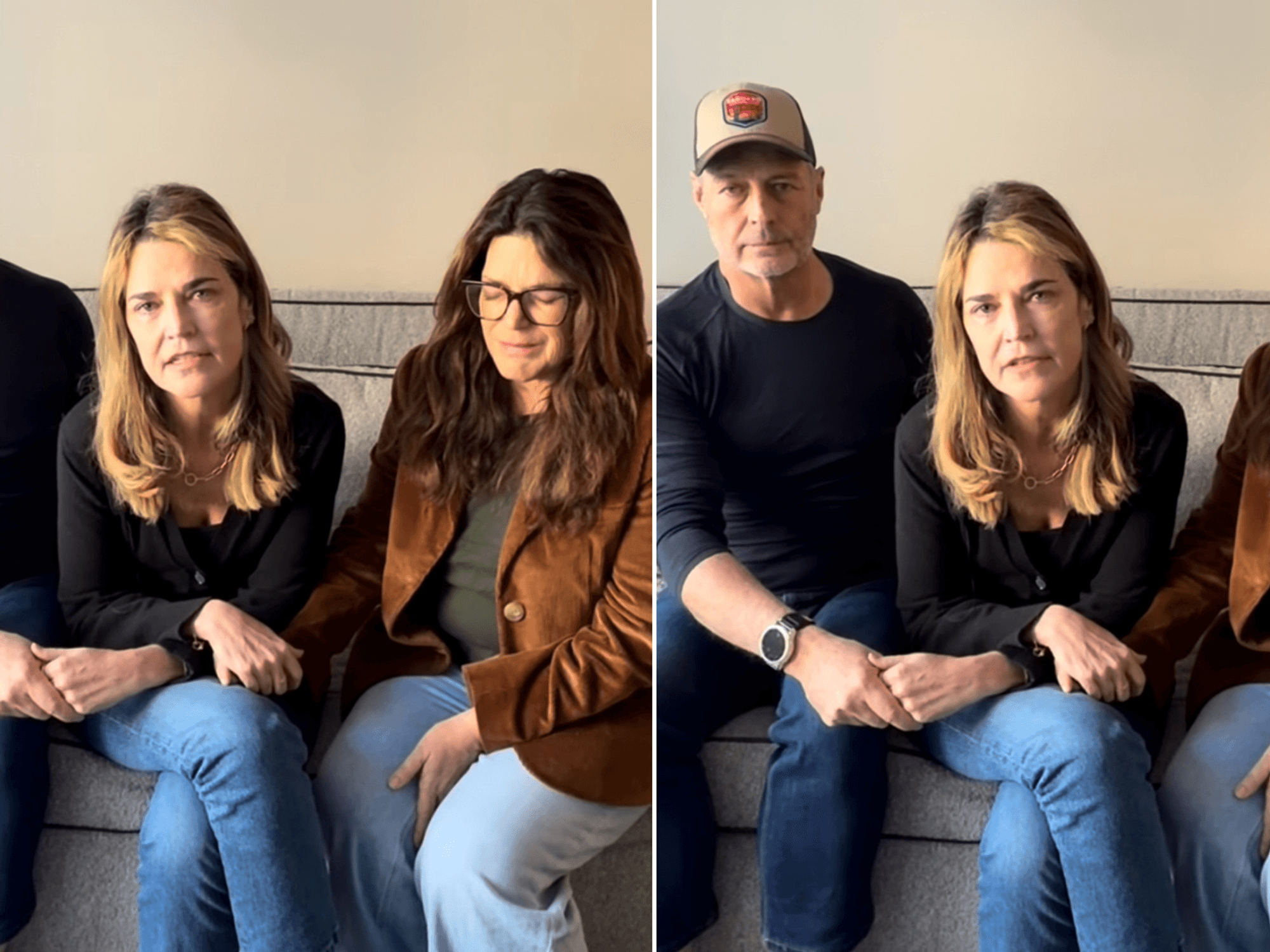

Labour councillor Stuart Fawcett says if we want national renewal for Britain, we must rebuild the family

Don't Miss

Most Read

Trending on GB News

The lifting of the two-child benefit cap last week has forced a wider national reckoning that has been a long time coming.

It should prompt us to look beyond the narrow confines of welfare arithmetic and confront a deeper, more uncomfortable truth: the British family-once the defining social institution of our culture-is in fundamental decline.

It needs a renewal of cultural and financial investment from the state to become the bedrock of stability and social mobility once again.

Critics of removing the two-child benefit cap often say, “people shouldn’t have children if they can’t afford them.” Well-young people are taking that advice. They’re choosing not to have children at all. And unless we face that, Britain’s future will be poorer for it.

TRENDING

Stories

Videos

Your Say

Our birth rate has now fallen to its lowest level on record. We frequently talk about demographic change, economic stagnation, and the pressures on public services, but rarely about the underlying cultural shift that links them all: our society has quietly become economically and structurally anti-family. For many young people, the idea of forming a family is no longer a natural life step, but an unaffordable luxury.

Fifty years ago, most families lived on a single income. Today, almost every household needs two full-time salaries just to stay afloat - but our culture and workplaces haven’t adjusted accordingly. We still assume one parent can absorb the childcare and domestic load, an expectation that overwhelmingly falls on women. As a result, women pay the price through reduced earnings, slower progression and lasting financial penalties when they have children.

At the same time, the backbone of support that families traditionally provide-the steadfast dependability that no welfare system can match-has been eroded. Ironically, the Conservative welfare reforms of the last decade were partly driven by an ambition that families should provide more mutual support rather than relying on the state. However, by then, the fabric of family life in the UK was not robust enough to take on this mantle and the results are now beginning to show.

Their vision overlooked a central reality: the modern cost-of-living situation requires two full-time incomes just to stay afloat. Home and family management was not only devalued but priced out. The single-income, life-long, and cohesive “family unit” they wanted to rely upon no longer existed in large parts of Britain. Indeed, it is now often remarked that the single greatest impact of the Government’s new breakfast clubs is not just resolving hunger but bridging childcare gaps for working parents who work all hours to provide for their families.

When family breaks down, the consequences fall hardest on children. I’ve seen the realities of that at crisis point; it is traumatising for children and expensive for the state.

Before entering politics, I was a therapeutic foster parent. I saw first-hand the impossible decisions social workers have to make, and the flawed assumptions that still shape our social care system.

The guiding principle handed down for decades has been: “the best place for a child is always the family home.” Except-it often isn’t. For some children, the family home is the source of harm, neglect or trauma. And when the state hesitates to intervene early enough, that trauma becomes the seed of the next generation’s problems.

If we truly want to protect children and rebuild families, the state must take a far more proactive role. That means intervening earlier, more consistently, and without fear of political criticism about “state overreach.” But it also means confronting the structural failure that currently prevents intervention: we simply do not have enough foster carers in Britain.

Sadly, the vocation is not seen as a valued career-something I sincerely lament and would like to see change. Foster parents deserve equal respect for their contribution to our society among other mainstream career choices.

Breaking intergenerational cycles is the single greatest investment we can make in the future of our society. And that starts with recognising that measures like child benefits are not handouts: they are often efficient, preventative tools. Every pound spent supporting families-through breakfast clubs, early-years support, parental financial assistance or targeted welfare-is many pounds saved in future social care, police time, court proceedings, mental-health interventions and long-term economic inactivity.

If we want national renewal for Britain, we must rebuild the family. Not by retreating into nostalgia or moralising, but by acknowledging reality: families today cannot function without cultural recognition alongside social and economic support.

Last week’s change to welfare policy marks the beginning of a new chapter- one that supports parents, seeks to protect children from their choices, and rebuilds the social fabric through family life. Britain can be great again, but only if we understand that the health and prosperity of the nation begins, and ends, in the family home.

More From GB News