I'm extremely worried that the wrong lessons have been drawn from the violence in Ballymena - Kevin Foster

Violence can never be justified, but we must heed the warnings

Don't Miss

Most Read

Trending on GB News

You don’t make a valid point on Immigration Policy by throwing a petrol bomb at the Police. The rank-and-file officers who serve in the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) do a difficult and dangerous job.

They often find themselves on the receiving end of violence born out of sectarian politics or political decisions they have had no part in. They deserve our thanks and admiration for their bravery.

In response to the recent disorder, Assistant Chief Constable (ACC) Ryan Henderson of the PSNI condemned the recent violence in Ballymena as "racist thuggery, pure and simple".

He stated the attacks were "clearly racially motivated" and should be "loudly condemned by all right-thinking people", whilst any attempt to justify or explain the violence as something else was "misplaced."

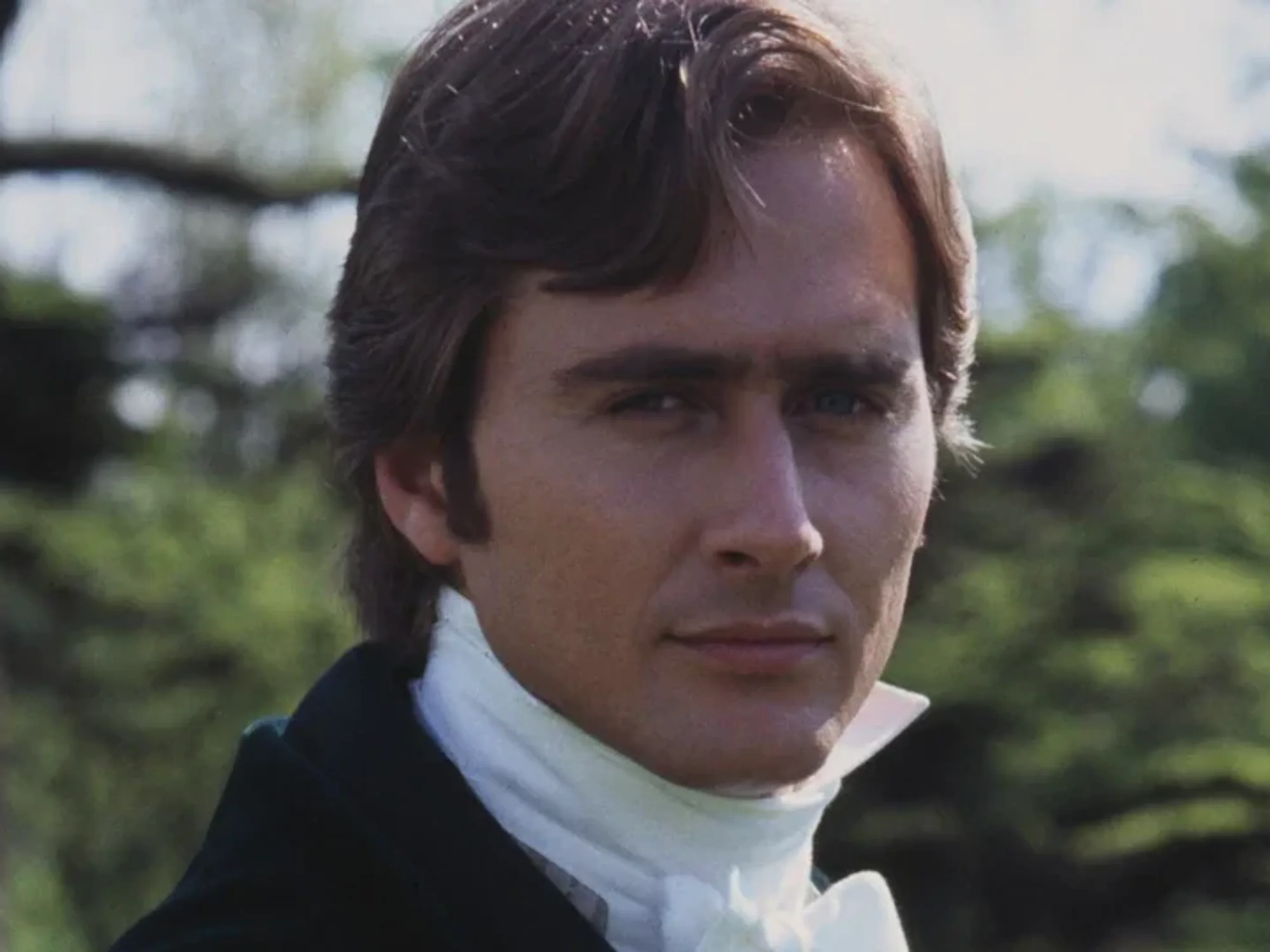

I'm extremely worried that the wrong lessons have been drawn from the violence in Ballymena - Kevin Foster

I'm extremely worried that the wrong lessons have been drawn from the violence in Ballymena - Kevin FosterYet GB News viewers can both loudly condemn violent attacks on brave police officers, whilst also asking for an explanation as to why there has been violence in Ballymena.

This is not to justify violence, but to see what lessons can be learned or what wider warnings are being given by recent events.

The flash point in Ballymena was the alleged sexual assault of a teenage girl by two men, with a planned peaceful vigil being followed by violence.

Some suggested this is because in Irish culture, women are held in high esteem. Yet in the past, many were all too prepared to ignore the scandals of the Magdalene Laundries and other abuses of women’s rights. This alone does not explain the violence.

Where we might see a unique Ulster aspect is in the loyalist fear of their communities being betrayed and overwhelmed, dating back to before the Home Rule debates.

A deep-rooted fear the British state will not stand up for them when needed, they must do it themselves, with asylum seekers being housed in their communities by the British Government becoming the latest flash point for this concern.

Yet if there is not a unique Northern Irish aspect to the recent violence, this worryingly indicates we might see more of the type of disorder we have seen in Ballymena across the United Kingdom as the Government seeks to shift more asylum seekers out of hotels and into rented housing dispersed across the country.

The Chancellor’s recent spending review set the goal of ending the use of asylum hotels; few would argue with this, although many queried why it will take another four years to do so.

Yet unless Labour changes course and builds large asylum accommodation centres or vastly increases the deportation rate of failed asylum seekers, most will be relocated into working-class communities across Britain.

As of the most recent figures, around 32,000 asylum seekers are currently housed in hotels across the UK, yet this hides a regional disparity. In London, 65 per cent of asylum seekers are housed in hotels, and in the South East, 59 per cent of asylum seekers are housed in hotels.

Anyone with even a basic knowledge of the UK’s housing market will instantly realise they are unlikely to be rehoused there, especially once you add the impact of soaring numbers of new small boat arrivals.

Moving asylum seekers from hotels into dispersal housing will inevitably mean a major net transfer of them to the North and Midlands, in areas where rented accommodation is cheaper and often amongst communities like Ballymena.

Metropolitan elites rarely live next door to the outcome of their views on crime, immigration and asylum. It’s those living in working-class communities like Ballymena, whose views and concerns they ignore, who do, often leaving them feeling voiceless in the democratic process.