Full list of stealth tax options Rachel Reeves could target in Budget as Income Tax hike ruled out

Finance expert discusses Reeves' use of 'stealth taxes'.mp4 |

GB News

After an Income Tax U-turn in Downing Street, Rachel Reeves may use stealth taxes to plug £40billion fiscal gap

Don't Miss

Most Read

Chancellor Rachel Reeves has abandoned plans to raise headline income tax rates ahead of the November 26 Budget.

However, with a £40billion black hole to fill, officials and tax specialists now expect a package of less visible threshold and base adjustments, so-called “stealth” taxes, designed to increase revenue without altering headline rates.

GB News has taken a look at alternative measures that could be implemented, how they would operate, who would be affected, and the political implications.

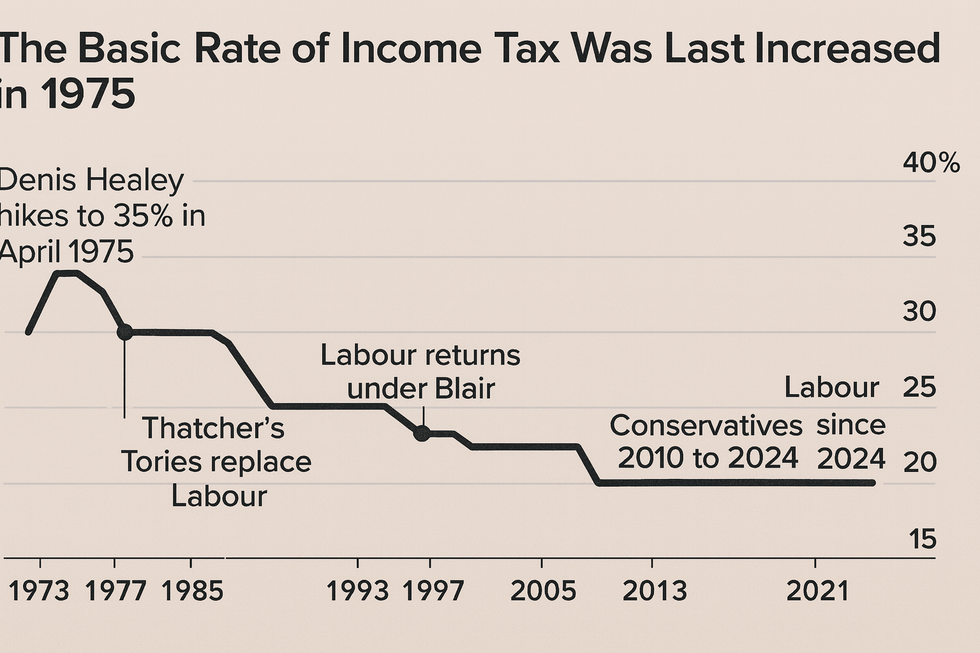

1. Extend or tighten the freeze on Income Tax and National Insurance thresholds

What it does: Keeps the personal allowance, higher-rate thresholds and National Insurance bands at current levels, allowing wage inflation to pull more individuals into higher tax brackets.

Likely yield: Several billions per year, with a two-year extension frequently cited by analysts as raising around £8billion annually.

Who pays: A broad range of employees and pensioners, with middle-income households most exposed as real thresholds fall.

Politics: Marketed as avoiding rate increases, but regressive in impact. Simple to implement and the quickest option available to the Treasury.

TRENDING

Stories

Videos

Your Say

2. Cut the higher-rate Income Tax threshold

What it does: Lowers the point at which the higher income tax rate applies.

Likely yield: Higher than a freeze, increasing receipts from middle and upper-middle earners.

Who pays: Higher earners and professionals, with some middle-income workers moving into the higher band.

Politics: More visible than freezing thresholds and likely to cause concern in suburban and commuter constituencies.

3. Tighten pension tax reliefs and reduce the tax-free lump sum

What it does: Reduces the maximum tax-free lump sum and places new limits on contribution and annual allowance reliefs.

Likely yield: Significant over time, particularly from higher earners and larger pension pots.

Who pays: Wealthier savers and some retirees with mid-sized pots if lump-sum changes apply broadly.

Politics: Can be presented as a fairness measure but sensitive among older voters.

The Chancellor is expected to target stealth taxes

|GETTY

4. Reform Capital Gains Tax and cut the annual allowance

What it does: Lowers the Capital Gains Tax (CPT) exemption and could align CGT rates more closely with income tax rates.

Likely yield: Potentially substantial, particularly from investment and property disposals.

Who pays: Investors, landlords and wealthier households.

Politics: Attractive to Labour’s base as a tax on wealth, but may spark concerns over capital flows.

5. Property taxes: Council Tax reform, band multipliers, mansion tax, Stamp Duty changes

What it does: Revalues council tax bands or applies higher multipliers on bands G and H; introduces a one per cent annual levy on very high-value homes; retargets stamp duty thresholds for high-value transactions.

Likely yield: Mid-billions from combined measures.

Who pays: Owners of high-value homes, second-home owners and buyers in the southeast.

Politics: Viable; can be framed as targeting wealth but risks local opposition.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS

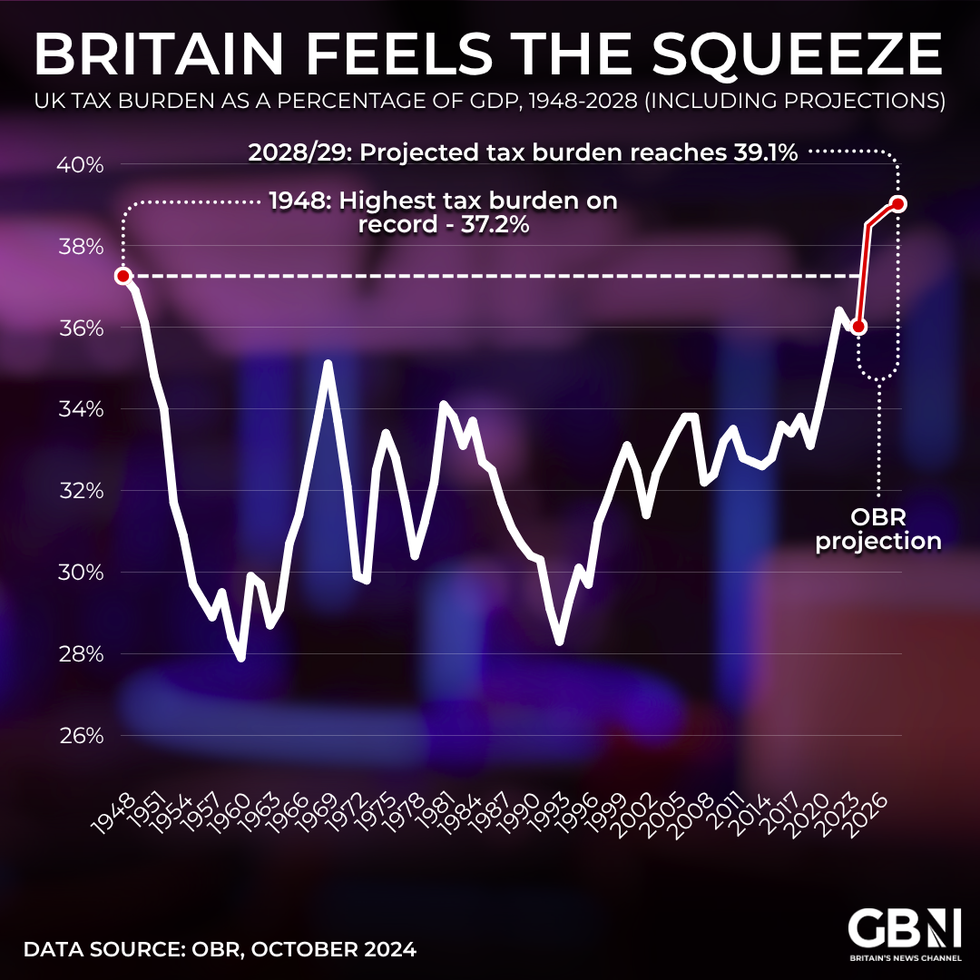

UK tax burden as a percentage of GDP | GB News

UK tax burden as a percentage of GDP | GB News6. New or higher taxes on landlords and rental income

What it does: Applies National Insurance to rental profits or imposes higher surcharges, alongside tighter deductions.

Likely yield: A meaningful uplift from the buy-to-let sector, with some smaller landlords facing sharply higher tax bills.

Who pays: Small and large landlords; possible knock-on effects for tenants through rent increases.

Politics: Politically saleable but could fuel criticism over rising housing costs.

7. Reduce VAT exemptions or narrow reduced-rate rules

What it does: Removes certain exemptions, narrows zero-rate categories or raises reduced rates.

Likely yield: Broad-based and steady.

Who pays: Consumers, particularly households that spend more on services affected by rule changes.

Politics: Politically risky due to cost-of-living pressures; likely confined to luxury or specialist sectors.

8. Lower the VAT registration threshold

What it does: Brings more small businesses into the VAT system by reducing the threshold, for example from £90,000 to around £30,000.

Likely yield: Significant in aggregate.

Who pays: Small businesses, with costs possibly passed on to customers.

Politics: Unpopular with SMEs but can be presented as modernising the VAT system.

9. Inheritance Tax tightening

What it does: Extends exemption periods, restricts business and agricultural reliefs and accelerates tapering.

Likely yield: Moderate to significant.

Who pays: Heirs of larger estates and business or landowners who use reliefs.

Politics: Framed as tackling inter-generational wealth; sensitive for rural and business communities.

10. Wealth levies or one-off windfall taxes

What it does: Imposes temporary or recurring levies on high net-worth households or specific asset classes.

Likely yield: Potentially high but subject to avoidance risks.

Who pays: The ultra-wealthy.

Politics: Popular with voters but difficult to enforce and politically complex.

11. Sector-specific and corporate base-broadening measures

What it does: Introduces levies on digital platforms, banks or energy producers, and strengthens rules against profit shifting.

Likely yield: Moderate to significant.

Who pays: Corporations and high-profit industries.

Politics: Publicly saleable but likely to trigger business lobbying.

12. Environmental and usage charges

What it does: Reverses fuel duty freezes, introduces electric-vehicle mileage charges and raises congestion or ULEZ-style fees.

Likely yield: Modest to moderate.

Who pays: Drivers and vehicle owners.

Politics: Positioned as environmental policy; risks backlash if poorly targeted.

13. Anti-avoidance and enforcement expansion

What it does: Closes loopholes, restricts generous reliefs and expands HMRC’s enforcement capacity.

Likely yield: Gradual increases over time.

Who pays: Users of complex tax structures, including multinational firms and high-net-worth individuals.

Politics: Low controversy and strong public support; requires upfront investment.

14. Changes to business structures and partnership taxation

What it does: Aligns partnership National Insurance treatment more closely with employed workers and increases employer-equivalent charges.

Likely yield: Around £1–2billion, according to specialist estimates.

Who pays: Partners, consultants and some SME owners.

Politics: Technically defensible but contentious among small-business groups.

Bowmore’s analysis finds 720,000 people, about 65 per cent of current top‑rate taxpayers, now pay the 45% rate because of fiscal drag; only 385,000 (35 per cent) would qualify if the band had risen with inflation.

John Clamp, Fellow of the Personal Finance Society and Chartered Financial Planner at Bowmore Financial Planning, said: “Both the 45 per cent and 40 per cent rate of income tax are capturing more and more taxpayers.

"A lot of people who consider themselves as having very little disposable income are now finding that they are having to pay the very highest rate of income tax."

The Chancellor is now expected to leave Income Tax raising proposals

|CoPilot/Institute for Fiscal Studies

Mr Clamp added: “Many see fiscal drag as a hidden stealth tax.

"The Government is content to let inflation do its work and add more and more people to the highest tax rate.

"Many people are working harder but taking home less, simply because inflation has drawn them into higher tax bands.”

On economic consequences he warned: “It’s perhaps unsurprising productivity is stagnating. If extra work barely boosts take‑home pay because of frozen tax bands, people are less inclined to work longer hours or push themselves — and that ultimately drags on the economy.”

More From GB News