Describing rural folk as ‘racist’ is an insult to what happened to my sister in Bradford - Colin Brazier

Racism is a regrettably universal hallmark of the human condition

Don't Miss

Most Read

Trending on GB News

In the early 1990s, my late wife shared a flat in Ealing with a black South African who occasionally announced that she was feeling “ethnically stressed”.

By which - I think - she meant there were too many white faces around and she needed to situate herself, briefly, somewhere that reminded her of home.

Her answer was to travel to the neighbouring (and infinitely diverse) West London suburb of Southall, presumably in search of the respite that only comes from being amongst people who share similar skin pigments.

This sentiment struck me at the time as revelatory - coming, as it apparently did, from the mouth of a black woman, who would not consider herself remotely racist.

But, if true (and my late wife is no longer around to ask), it accords with what many of us suspect. Where people choose to live may say something about their values; who they feel comfortable sharing a community with; where they want to raise children, grow old, and die.

I thought about this idea of “ethnic stress” when we witnessed this week, the latest assault on the English countryside by the race-grievance industry. It came in the form of a report from Leicester University’s Centre for Hate Studies.

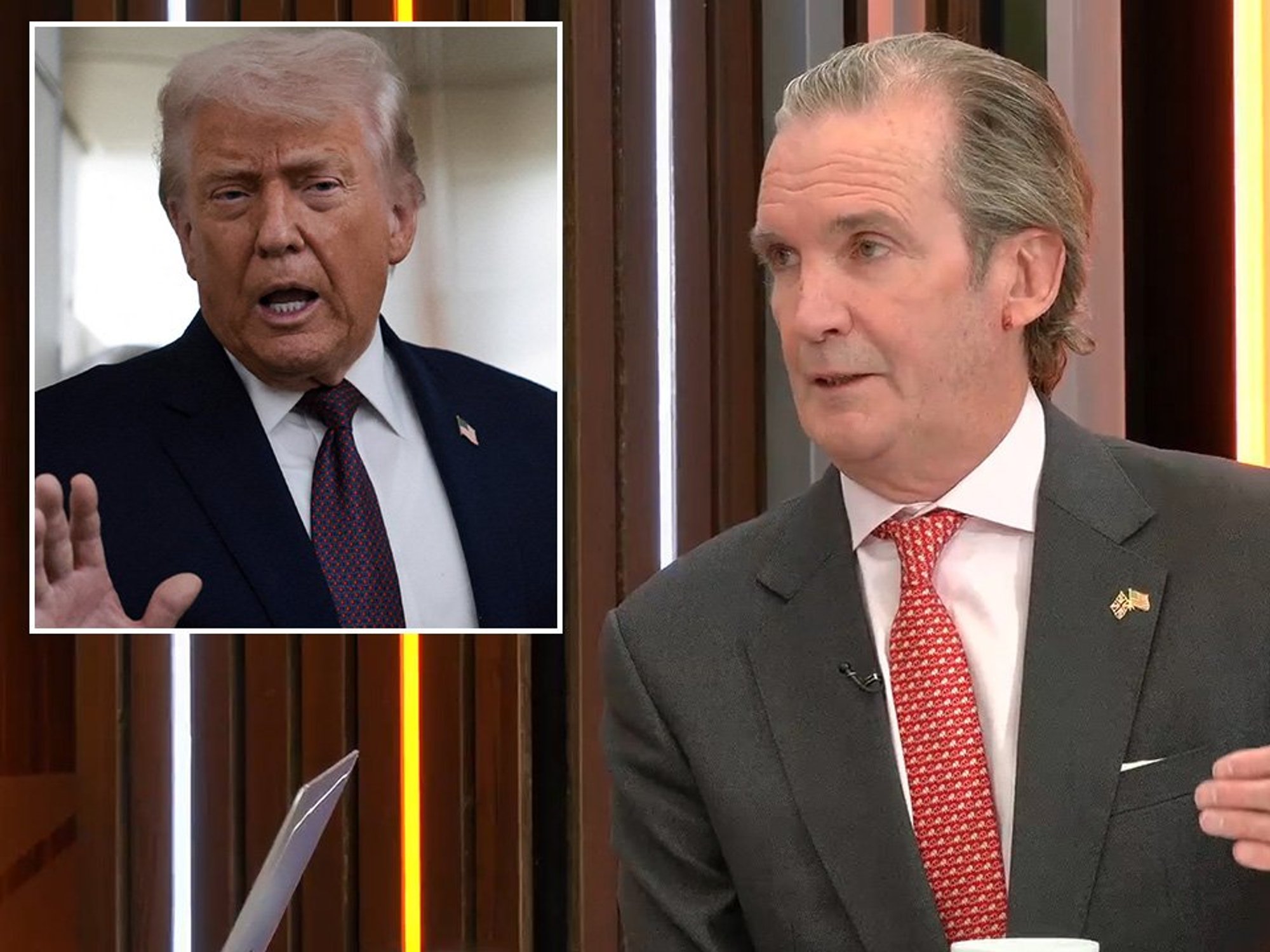

Describing rural folk as ‘racist’ is an insult to what happened to my sister in Bradford - Colin Brazier |

Describing rural folk as ‘racist’ is an insult to what happened to my sister in Bradford - Colin Brazier | Getty Images

The mere fact that British academia harbours entities with titles like ‘Centre for Hate Studies’ tells us quite a lot about the ideological orientation of higher education.

Since it was formed a decade ago, I suspect the CFHS has shown a marked reluctance to investigate the ‘wrong kind of hate’.

The kind of disdain directed, for instance, at Britons like my sister at her check-out till at the Co-Op in Bradford. On more than one occasion, a customer has called her a “white bitch” (or variation thereof).

I believe (and from personal experience, my sister knows) that racism is a regrettably universal hallmark of the human condition, rather than a prejudice only wielded and weaponised by white folk.

But let us, for a moment, suspend our disbelief and accept that the word ‘hate’ can be used objectively by academics. What, then, are we to make of Leicester University’s assertion that “racism in rural England is getting worse” and that the countryside’s indigenous inhabitants need to snap to it and ensure there are more prayer rooms and halal outlets for visiting Muslims (both suggestions in the report).

I believe the researchers when they say that non-whites arriving in the countryside sometimes face ‘micro-aggressions’, including “staring” and “hostile body language”. When I first swapped London for a rural village nearly two decades ago, this was my experience too.

The countryside views everyone, not necessarily with suspicion, but with scepticism. An important distinction that derives from a collective memory that spans generations.

One which remembers hard times and tough winters and failed harvests and which, consequently, is less about meretricious show and more about doing.

Willingness to bend to local customs is prized, and newcomers are judged according to their actions and the contents of their character, and far less by secondary characteristics, like job title or skin colour.

A farming friend in North Yorkshire likes to point to Rishi Sunak, his local MP, as a good example of this principle. Yes, the former PM seems to epitomise rootless globalisation, with his Indian billionaire wife and banking career at Goldman Sachs.

But when the Sunaks moved to rural Richmondshire, they embraced its conventions up to and including sending their daughters to the local Pony Club.

His critics will say it was all for the cameras. My friend says not: Sunak, for him, is every bit as much countryman as he is Davos Man.

Come to the countryside and put your shoulder to the wheel, and you will be valued. My nearest petrol station - an absolute lifeline in rural communities - was taken over a couple of years ago by an Indian family.

They work hard, stock local farming produce and take the time to chat. This is how racism is undermined, not by hectoring countryfolk and labelling them all with the increasingly powerless curse-word “racist!”.

‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ goes the adage. But the Leicester University study insists, in spite of much evidence to the contrary, that the countryside is ethnically broken and must be fixed.

Its solutions? Bringing in more “diverse communities” to break up the “rural monoculture”, which might otherwise be a breeding ground for “right-wing sympathies”.

This is to ignore and subvert one of the great changes to rural Britain in recent decades. The countryside is already being transformed by house-building and an influx of city folk (like me), who do not always (unlike me) sign up to the existing mores of village life.

Many of these new arrivals are part of the white flight from once great cities, like Leicester, Bradford and London. The emigres have seen quite enough of the ‘enriching’ effects of mass migration and can’t wait to leave this democratically unsanctioned experiment behind.

For all that our elites wish it weren’t so, the ‘Great Sort’ is an observable phenomenon, as people, armed with ever-greater mobility, seek to live with people like themselves. In a democracy, this is our right: the right to freely associate with whom we like.

This is especially true in the countryside, which maintains a strong link with our history and atavistic traditions, for all that our cultural commissars try to pretend otherwise (my favourite example was the BBC drama Poldark, which insisted on putting black barmaids in coaching inns on 1700s Dartmoor).

But Leicester’s Centre for Hate report reveals another misapprehension. It sees the countryside, first and foremost, as an amenity, where accessibility is all.

We see this ideological modus operandi in other areas of public life, most obviously the NHS, which is routinely accused of being racist in its approach to ethnic minorities. However, the countryside is not a public service or playground for stressed city dwellers.

It is a living place where livings are made. Less so than was once the case, of course, but - the further you go away from the big conurbations - anything but a theme park.

Rural Britain has problems. Housing for locals, a shortage of agricultural labourers, and the ‘Surrey-fication’ of hitherto rural areas. Places which once had a slower and deeper pulse than suburbs and cities, but which now resound to the tempo of delivery drivers and commuters.

There is nothing new in the idea of the countryside facing change. The great William Cobbett campaigned about rural poverty 200 years ago.

He became what we would now call a firebrand left-wing MP. But he was also a farmer who rode around the countryside for his most famous book, Rural Rides, and possessed a keen eye for humbug. What would he make of a university making a collective slur against the ‘whiteness’ of the countryside?

He would surely suggest that Leicester, a city not-so-long-ago rocked by the sort of inter-communal ethnic violence more commonly seen on the Indian sub-continent, should look towards its own troubles, not to those of England’s pastures green.

More From GB News