The row over banning the burka gets to the very heart of the challenge facing Britain - Miriam Cates

Nigel Farage says face coverings in public ‘don’t make sense’ as he reacts to Sarah Pochin’s burka demand |

GB News

OPINION: We can have freedom of religion, or we can have social cohesion. We cannot have both

Don't Miss

Most Read

Trending on GB News

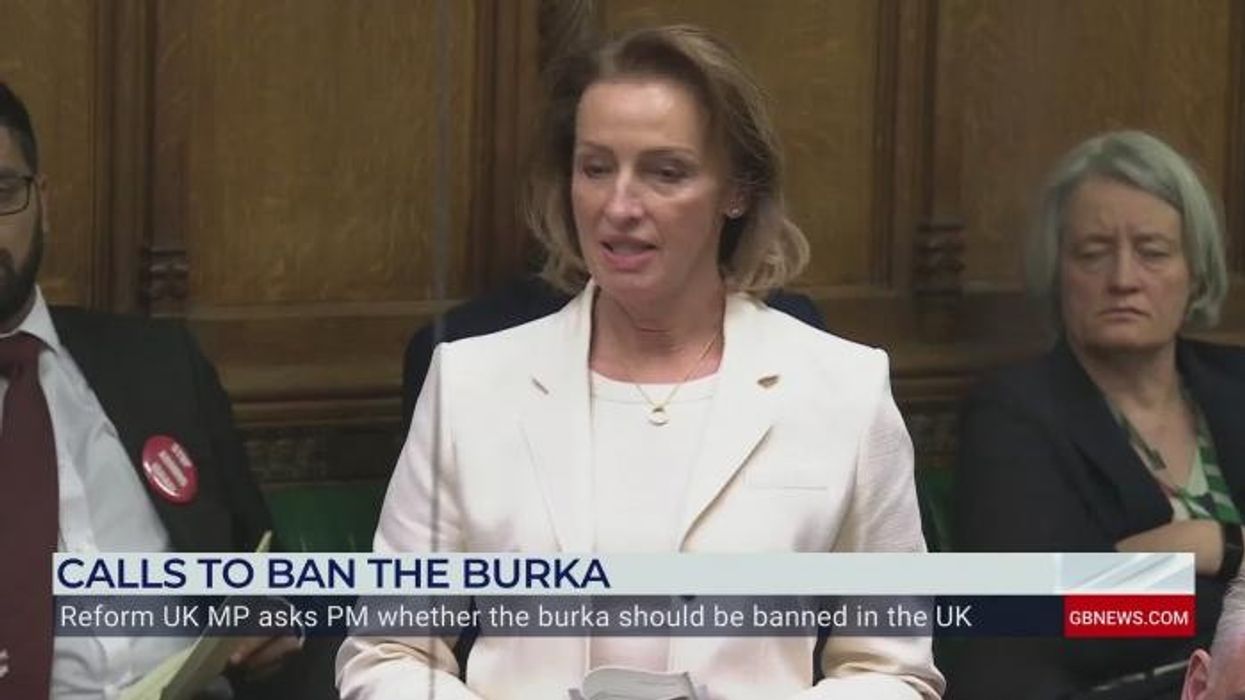

Prime Minister’s Question time can often be a rather dull affair, where MPs raise predictable queries about potholes in their constituencies and the Prime Minister reads out pre-prepared platitudes. But last week, Reform MP Sarah Pochin asked a question that sparked uproar in the House of Commons Chamber, caused the Chairman of her own Party to resign and fueled thousands of newspaper column inches.

Pochin’s question began blandly enough, asking the Prime Minister if he sought closer alignment with our European neighbours. But the Runcorn MP then took a controversial turn when she revealed that the alignment she was seeking was for the UK to follow the example of France, Denmark and Belgium and ban the burka.

In recent years, women dressed in burkas have become an increasingly common sight on the streets of Britain’s towns and cities. The burka is an extreme form of Islamic dress, which covers the whole of a woman’s body and face. The burka includes a narrow horizontal ‘window’ over the eyes, but even this is covered by a mesh so that no parts of the wearer’s body can be seen.

The niqab is a less severe form of the garment, this time leaving the eyes uncovered, and the hijab covers the head and neck but reveals the whole of a woman’s face.

As the size of Britain’s Muslim population grows, arguments over whether extreme forms of religious dress are compatible with social cohesion will only intensify. The current debate about whether or not women should be banned from wearing the burka cuts to the heart of some of the most important questions of our time; questions about the value of individual liberty, the importance of religious freedom and the success or failure of multiculturalism.

Those who argue for a burqa ban point to the security risk inherent in allowing individuals to conceal their identity in public. Whether for official purposes, such as at passport control in an airport or for more informal interactions in day-to-day life, it is important to be able to verify a person’s identity. Safe, successful societies—as Western cultures have historically been—are built on high levels of social trust. No one collaborates or does business with someone they don’t trust. And we can’t trust someone unless we know who they are.

The row over banning the burka gets to the very heart of the challenge facing Britain - Miriam Cates |

The row over banning the burka gets to the very heart of the challenge facing Britain - Miriam Cates | Getty Images

One of the ways that human beings have evolved to discern whether another person can be trusted is through facial expressions and the use or avoidance of eye contact. The split-second judgments that we make about whether an individual is friend or foe are not based on irrational prejudice but on highly developed and often very accurate experience-informed instincts. When the entirety of a person’s face and body are hidden from view, it is completely impossible to know whether that person is safe and can be trusted.

From the IRA balaclava to the marks used in London today to hide from immigration control, face coverings have been used throughout history by criminals who want to conceal their identity. As a full body cover, the burka offers an opportunity to hide not only the face but even weapons and bombs. A NATO report into Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) found that:

“Wearing the burqa is such a perfect way to hide or to be hidden that men have also worn the [burqa] to smuggle themselves and munitions through borders or other forbidden zones. Some men caught by Afghan border police had IED vests and some had AK-47s under their burqa.”

Concern about the use of burkas by terrorists has prompted a number of African countries—including Senegal, Cameroon and Chad—to ban the garment.

With European countries witnessing an increase in Islamic terror incidents over recent years, it is reasonable to assume that there is at least a possibility that a burka might be used in a future attack.

Yet security and trust are not the casualties of the burka. For our communities to flourish, even for the economy to grow, Britain needs a cohesive society. Social cohesion may sound like a woolly idea, but without it, communities cannot function. We often focus on the importance of the law, policing and regulations in making sure rules are followed. But the truth is that obeying the law is not enough; it is the shared values, common language and common purpose of both friends and strangers that keep the wheels of society turning.

A burka completely prohibits its wearer from any public interaction and therefore prevents all participation in society.

Other arguments against the burka include its role in suppressing women’s freedoms and covering up abuse. Many Muslim women are pressured – perhaps compelled – to wear the burka.

If a non-Muslim woman complained that her husband was forcing her to cover her face in public, it is conceivable that police may investigate it as a case of ‘coercive control’, something that was criminalised in 2015. And Islamic dress is not just a potential tool for coercion; it can also be used to cover up the signs of physical abuse, such as in the tragic case of murdered schoolgirl Sara Sharif.

There are many rational and compelling reasons to outlaw the burka. But there are sensible arguments against a ban, too.

Many commentators make the point that, in a free country, people should be allowed to wear whatever they want. Of course, as a general rule, we do not want the state to dictate to individuals what they can and can’t wear. But in almost all areas of life, we accept some restrictions on our individual freedoms for the common good. We already accept limits to the way we dress; it is illegal to be naked in public or to wear clothing emblazoned with threatening slogans.

Most shops ban motorcycle helmets from being worn on the premises. There are legitimate circumstances in which the law can dictate what individuals cannot wear. The question is whether the public and security benefits of a burka ban outweigh the costs to individual freedom.

Since the burka is an item of Islamic clothing, some argue that banning it would be an infringement of religious freedoms. This is true; if a woman or a community believes that wearing the burka is a fundamental tenet of following the Islamic religion, then a legal ban on wearing the garment would indeed impinge on religious freedom.

However, there are already a number of religious practices that are banned in the UK, for example, polygamy, female genital mutilation, and the burning of widows. All of these practices have been or are associated with foreign religious customs.

It is often said that Britain has a strong tradition of religious freedom. But our religious tolerance laws, dating back to the 1600s, were written with the aim of ensuring a peaceful coexistence between two slightly different forms of the same Christian religion. These laws guaranteeing freedom of worship were not introduced in order to allow the non-Christian, non-Western, anti-freedom practices of other religions to be imported into our public realm. Given the enormous differences between the Christianity on which our nation was founded and modern-day Islam, we face a dilemma. We can have freedom of religion, or we can have social cohesion. We cannot have both.

Although the arguments in favour of banning the burka are strong, we should not dismiss those who oppose such a move. In the light of recent government authoritarianism during the Covid pandemic, we should not underestimate the potential for state overreach, and we should be cautious about introducing any restrictions on individual freedoms.

Perhaps the strongest argument against a burka ban is the enormous political capital that such legislation would consume at a time when the most important task of government is to drastically reduce immigration. This would have a far more lasting impact on social cohesion than banning the burka.

But, practicalities aside, we should follow other European countries—and indeed African and Asian ones—in banning the burka. In some ways, it's quite extraordinary that we ever allowed such a garment to be worn in a society that places such high value on social trust. But as with so many other cracks in British society, this is a lesson in the tyranny of tolerance.

In physics and engineering, the term “tolerance” is used to define how much deviation from the norm is possible before a piece of equipment becomes dysfunctional. Of course, we should tolerate a certain level of diversity and difference within British society. But once the extremes are given equivalence to the norm, diversity becomes destructive. Diversity is not always a ‘strength’; sometimes it can be a cause of social breakdown. The burqa is one such example.

More From GB News