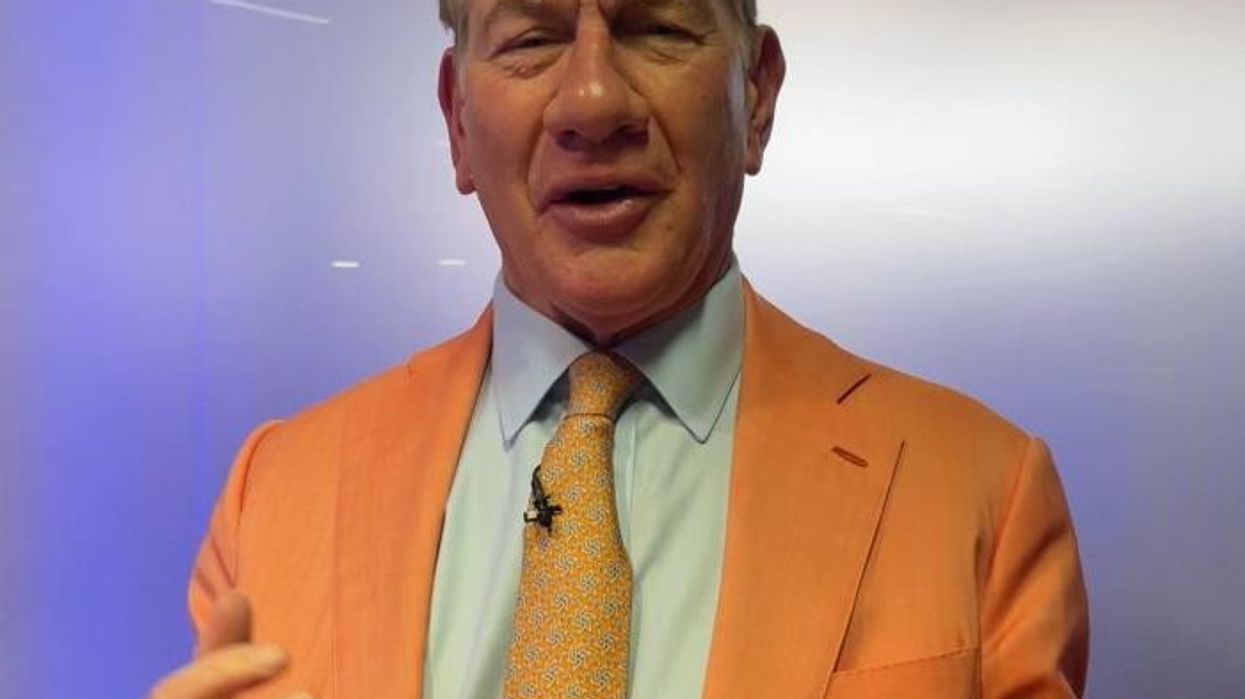

The Orgreave inquiry is a desperate attempt to throw the hard Left a bone. It won't work - Colin Brazier

The Left can’t agree on much - but they can all sign up to hating Margaret Thatcher

Don't Miss

Most Read

Trending on GB News

Lefties of a certain age all agree on one thing. Margaret Thatcher was evil. Not misguided, duplicitous or unscrupulous. But plain wicked.

It is often said that one of the problems with politics today is that those with whom we disagree no longer see ideological opponents as wrong, but bad. We think of it as a problem that started on the internet. In reality, it started before then. It started with Thatcher.

I remember reporting from her funeral in 2013. There were huge crowds of respectful mourners. But there are also smaller protest groups. We filmed one man of a certain age gleefully chanting “Maggie, Maggie, Maggie…Dead, Dead, Dead”.

In a free country, people have the right to be offensive. And that includes the right to - noisily - speak ill of the dead. But it was a moment which crystallised for me why the Left needed to hate Margaret Thatcher.

They are so riven by splits, between hardline socialists and social democrat Blairites, that they desperately need One Big Thing they can all coalesce around. And that is our first female Prime Minister. She may have stood down 34 years ago, but the years have not dimmed her role as a lightning conductor. For angry lefties, she is the gift that keeps on giving.

The Orgreave inquiry is a desperate attempt to throw the hard Left a bone. It won't work - Colin Brazier

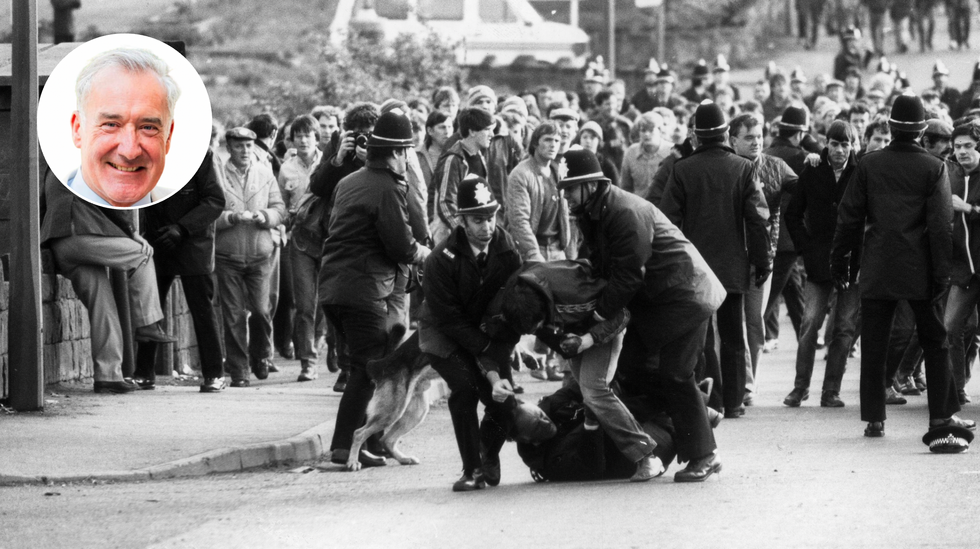

|Getty Images

How else can we account for the announcement this week that there will be a Public Inquiry into public order disturbances at the Orgreave coking plant in, wait for it, 1984. Many of those involved - both striking coal miners and police officers - are no longer alive.

It is, after all, 41 years since flying pickets from the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) tried to stop deliveries of coke from going to the steel furnaces at Scunthorpe. It was a life-or-death struggle for both Thatcher and her nemesis, Arthur Scargill.

In 1972, his union had succeeded in closing a similar coking plant, Saltley, fatally wounding a previous Tory leader, Edward Heath, who had sought to challenge the growing power of militant trade unions.

This time, the coking plant stayed open, and the die was cast. Scargill eventually climbed down and Thatcher ‘won’. Like many, I am uncomfortable with what happened next.

The wholesale closure of coal mines and the collapse of the communities which supported them. But at Orgreave, as at the scene of other industrial disputes in the 1980s, it was important that the unions should not be allowed to unlawfully inhibit the right to work and trade.

But for those on the Left, that right was not won fairly. On one especially violent day at Orgreave, more than 100 miners were injured. Dozens were arrested, although charges against them were later dropped.

In turn, and particularly after the Hillsborough disaster, it became an article of faith on the Left that South Yorkshire police, and quite possibly Thatcher herself, had sought to bend the law for political purposes.

And so, we will now have a Public Inquiry. It’s true that Labour promised some sort of investigation into Orgreave in its election manifesto, though not necessarily a full-blown Public Inquiry costing many millions of pounds. It will be chaired, not by a judge, but by a Church of England Bishop. One who has previously tweeted criticism of the Tories.

The 1980s were a time of hideous tragedy. Not just Hillsborough (97 dead), but the Piper Alpha oil rig (167 dead), Herald of Free Enterprise ferry (193 dead), Kings Cross fire (31 dead) and Clapham train crash (35 dead).

I have written before about my escape from the Bradford football stadium fire (56 dead), and it, deservedly was the subject of a public inquiry (although the decision to bracket it with the fatal disturbances caused by football hooliganism the same day stuck in many a craw).

Orgreave resulted in no fatalities. In fact, the only person whose death was linked to the miners’ strike was a taxi driver taking two working miners to a pit in the Welsh valleys. He was killed when pickets dropped a breeze block on his car from a bridge as it passed beneath.

So, why then is there to be an expensive public inquiry into Orgreave? What lessons can be learned 41 years after the event?

The time that has elapsed means that no officials in place today could face any repercussions. You might as well have an inquiry into the riots of Cable Street or Tonypandy.

No, this is grievance archaeology, pure and simple. Designed to keep the flame of hate for Thatcher burning bright and install Orgreave in the pantheon of Left-wing mythology. A Peterloo massacre for the 20th century, just without the body bags.

Of course, on hearing the announcement of a public inquiry, the National Union of Mineworkers declared that the news was “hugely welcome”. It will certainly be welcome for a union in need of relevance today. In 1920, the NUM had nearly a million members. Now it has about 100.

It’s fair to assume it would be less welcoming of a full public inquiry into the miners’ strike of the 1980s as a whole. As Margaret Thatcher’s official biographer, Charles Moore, pointed out this week, any such inquiry would seek “to establish the full facts about how Arthur Scargill got money from Gaddafi’s Libya and was promised it by the Soviet Union”.

But, just as history is written by the victors, so the terms of reference for public inquiries, indeed the decision to hold one at all (Theresa May rejected calls for an Orgreave inquiry in 2016), are dictated by who is in charge.

Labour is in government and gets to cherry-pick which historical events deserve a huge dollop of media attention. But the context is everything. Right now, Labour is having to tack hard towards Reform on many topics and risks alienating its more Left-wing supporters. An Orgreave inquiry is a bone thrown in their direction.

In reality, there are areas of public life in Britain crying out for public inquiries, with all the powers to compel witnesses to give evidence that such a process entails. It’s striking that the rape gang investigations do not have anything like this scope.

And, frankly, if you were looking at the events of 1984 in Yorkshire, you could find events which have more far relevance to the world we live in 41 years later. Where lessons really could be learned.

It was in 1984, for instance, that a headmaster in Bradford blew the whistle on the dangerous downsides of multiculturalism.

He wrote an article for a conservative magazine called The Salisbury Review (declaration of interest: I am now its assistant editor). His piece led to protests at school and police protection.

Eventually, Honeyford was effectively forced from his job, an early example of what we have come to call ‘cancel culture’ and, as such, worth understanding today, even though it happened a generation ago.

More From GB News