Former Manchester City manager says clubs must do more to protect academy players

Are clubs doing enough to support players that don't make it?

Don't Miss

Most Read

While there has been an upsurge in the coaching, structure and management of football academies, the psychological aid given to youngsters remains far from ideal.

The Premier League Rules of Development allows for each club to register up to 250 youngsters in their academies. But of the players who join at the age of nine, only one per cent will make it to England’s elite league, while an even lesser figure will ever make a living from the game.

That being said, are football academies doing enough to manage expectations, and to prepare young players for alternative careers if they don’t make it? And what are clubs doing to help released players integrate back into the society?

The deaths of released academy players have led to more demands on clubs to provide better wellness programs for players. In 2013, Joshua Keir Lyons made the news for sad reasons. The former Tottenham youth player, who was once considered as a footballing prospect, was eventually released from the game and battled with anxiety up until his death. A coroner’s inquest into his death condemned the lack of support he received from the London club.

There was also the distressing news of 18-year-old Jeremy Wisten who had a promising career at Manchester City’s academy. The teenager, who was born in Malawi, played for City's elite youth squads after joining the club in 2016 but was released in 2019 after an injury stint. He was found hanged in his bedroom in October last year.

As more cases surface, experts have also called for football administrators to do more to protect the mental health of academy youngsters.

Former Manchester City academy coach and head of education and performance management Pete Lowe says many football academies generally ignored the psychological strain that players face simply because they didn’t believe in it.

“Every day I listened to the news where football is concerned or sport is concerned and something else comes up about a competitor, a performer, having an issue with anxiety and depression after being released from football from one club or another. In 2013, a young player took his own life, in 2020 in December at my old club, another young player took his own life, that's two players too many and that should never happen. So even if you didn't believe in this aspect of mental health or whatever, to find out two players have taken their own lives should make the game that we're now talking about stand up and take a little bit more notice.”

Former Manchester City academy coach and head of education and performance management Pete Lowe

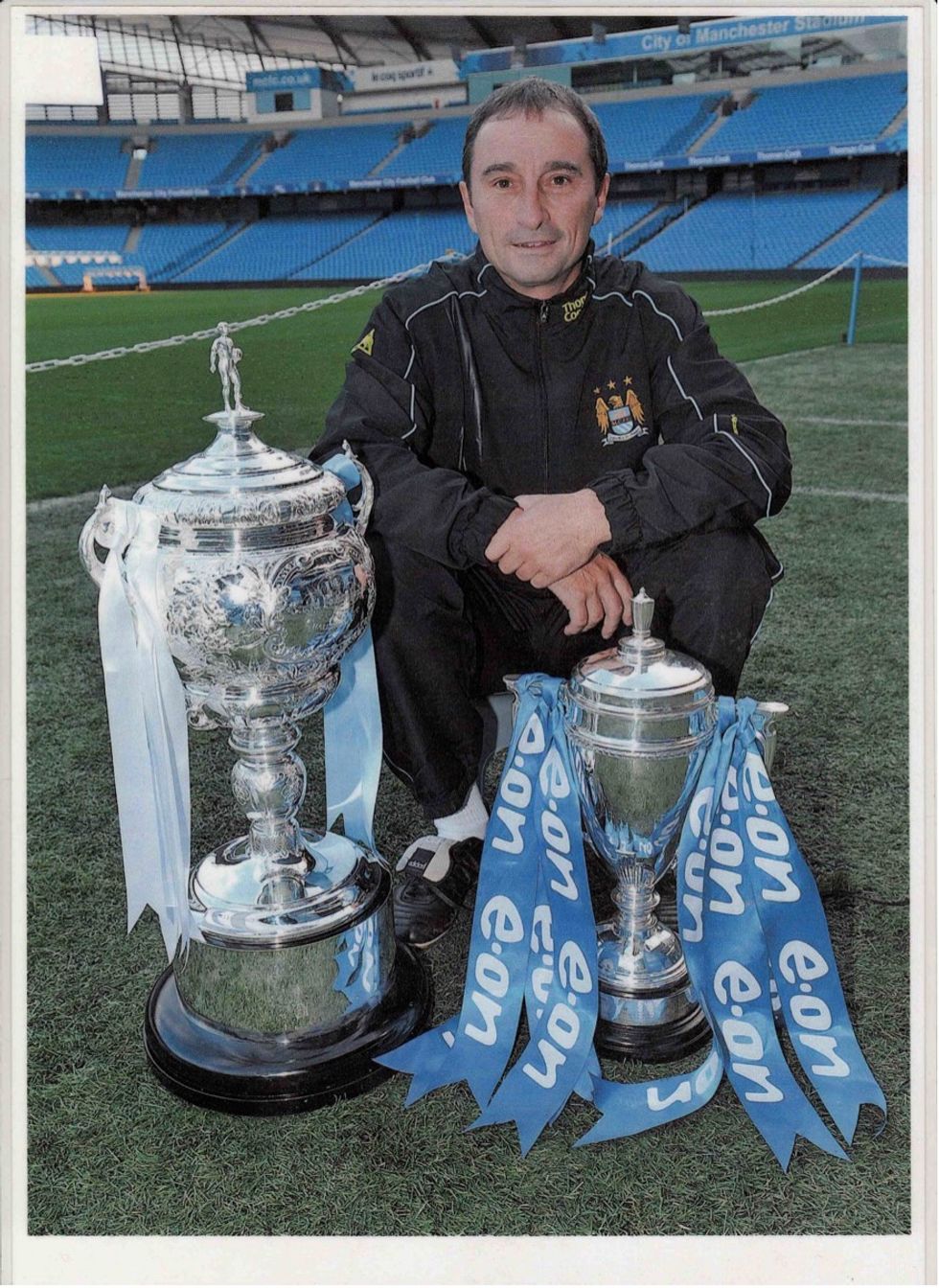

Pete spent 13 years working within a senior role at Manchester City where he was responsible for a side that produced 39 first team footballers and 25 international players. The team’s trophy cabinet further attests his success as they won 13 European tournaments, six Divisional Premier League Championships, an U16 Championship World Cup and an FA Youth Cup within a ten-years period.

He added that due to the ever-competitive nature of the sport, more players are getting released but clubs have a duty to help manage expectations and pressure, also adding that clubs must be communicative at each stage of a player’s transitioning.

“In terms of the players that get released from the game, the ones that have these problems are the ones that didn’t know that they really weren't doing that well and suddenly it's dropped on them that they’re no longer wanted (by the club). So, if a player thinks about that one day he's wanted at the club and then the next day he's not wanted, in a young person's life, that's a catastrophe that his world has been shattered overnight. All these dreams have been taken away from him and that's so hard to deal with.”

He noted that every staff within an academy setup must have some psychological experience and to be intentional about fostering a better understanding of the players in their care.

“What I mean by that is people that work with young players should understand young players. It's their responsibility to understand young players, plain and simple. Your responsibility as a member of staff is to understand those young people. Do I think we could have done better in the past? Yes. Without a question, we got things. When I look back now, I'll go, you know, I think we got some things wrong.”

“Football has a responsibility and everybody who works with a player, particularly young players, or even fully fledged professionals should know that just because they are men, doesn’t mean to say that they don’t need help. Everybody needs help at some stage. The secret is knowing when, how aware and how to deliver it.”

Pete left Manchester City as part of a massive exodus at the club, and currently works as the director of PlayersNet, an independent, not-for-profit organisation that deals with former and current players and volunteers on metal wellness and psychological issues.