Buckle up Britons, a once-in-a-generation assault on the established order is coming - Paul Embery

Buckle up Britons, a once-in-a-generation assault on the established order is coming - Paul Embery

|Getty Images

The year 2026 may prove to be era-defining, writes trade union activist and writer Paul Embery

Don't Miss

Most Read

Trending on GB News

The next 12 months promise to be among the most intriguing in modern British political history.

The plunge in support for Labour and the Conservatives – who rarely now poll more than 40 per cent between them – is unprecedented.

Meanwhile, radical alternatives in the shape of Reform UK and the Greens, with their slick media operations and charismatic leaders, are making serious headway.

Might we be witnessing the death of two-party politics in Britain – or even the end of Labour and the Tories as serious political forces?

It’s a long shot – both parties do, after all, have a habit of defying predictions of their demise – but it isn’t entirely inconceivable.

One need only look to continental Europe to see how mainstream parties that once seemed a permanent fixture of the political landscape can go bust. And it’s usually because they lost touch with large numbers of voters and no longer shared, or even understood, their priorities.

There is nothing to say that such a phenomenon could not occur in Britain.

Labour in particular had better beware. The party has plunged to record lows in the polls and is saddled with a leader whose days look numbered. Barring a miraculous turnaround, Starmer will almost certainly not make it to the end of 2026.

Buckle up Britons, a once-in-a-generation assault on the established order is coming - Paul Embery | Getty Images

Buckle up Britons, a once-in-a-generation assault on the established order is coming - Paul Embery | Getty ImagesAndy Burnham has been on manoeuvres for some time and, assuming he secures a parliamentary seat, will be among the favourites to win any leadership contest. He would also, in my view, represent the party’s best hope of making an electoral recovery.

But even with a new leader, Labour will be doomed unless it can swiftly deliver economic growth and repair our broken immigration and asylum system. In opposition, the party pledged to do both these things. But after nearly 18 months in office, it has made insufficient progress.

There is no indication that the Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, understands what is needed to kickstart our economy. It certainly isn’t more of the Treasury orthodoxy that for nearly two decades has entrenched low growth and productivity.

Whacking up taxes and cutting public spending will prove counter-productive in the most literal sense. Instead, the government must use its massive fiscal capacity to rebuild our crumbling infrastructure and public services, invest in the productive sector and deliver full employment and higher wages. What is the point of a Labour government if it is not to do these things?

On immigration and asylum, ministers would point to recent figures showing a year-on-year drop in net migration of 69 per cent.

But the figures for the preceding couple of years were so colossal (in the upper hundreds of thousands) that even after a sharp reduction, the latest numbers remain, by historical standards, eye-wateringly high. The government must not be allowed to get away with presenting these figures as a ‘new normal’.

And still the small boats come.

Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood has at least displayed the radical thinking and courage necessary to get a grip on the situation. But it may be some time yet before her Denmark-style measures begin to have an impact – and, in any case, there is no guarantee that she won’t be blocked by a combination of the civil service ‘blob’, activist lawyers and objectors on her own benches.

Ordinarily, the main opposition party would be expected to reap the benefits of public disgruntlement with the government. But that isn’t happening.

After a shaky start, Kemi Badenoch is finding her feet and beginning to impress. But she is seriously hampered by the fact that voters still remember just how badly the Conservatives messed things up when they were in office. Whatever Badenoch’s personal appeal, the Tory brand remains toxic – and will remain so for a long time yet.

So with millions struggling to make ends meet financially and sensing a wider social decay across the country – encapsulated by the inability of the State to control who comes into the country – the hostility towards the old establishment parties, which they deem responsible for the decline, remains palpable.

The next year will almost certainly see a deepening of existing social tensions and growing support for national-populist ideology.

The politics of liberal-progressivism, which still dominate throughout our political, cultural, corporate and academic institutions, will continue to meet with resistance – most likely through further street protests, the raising of national flags in local communities, and increased support for Reform UK and figures such as Tommy Robinson.

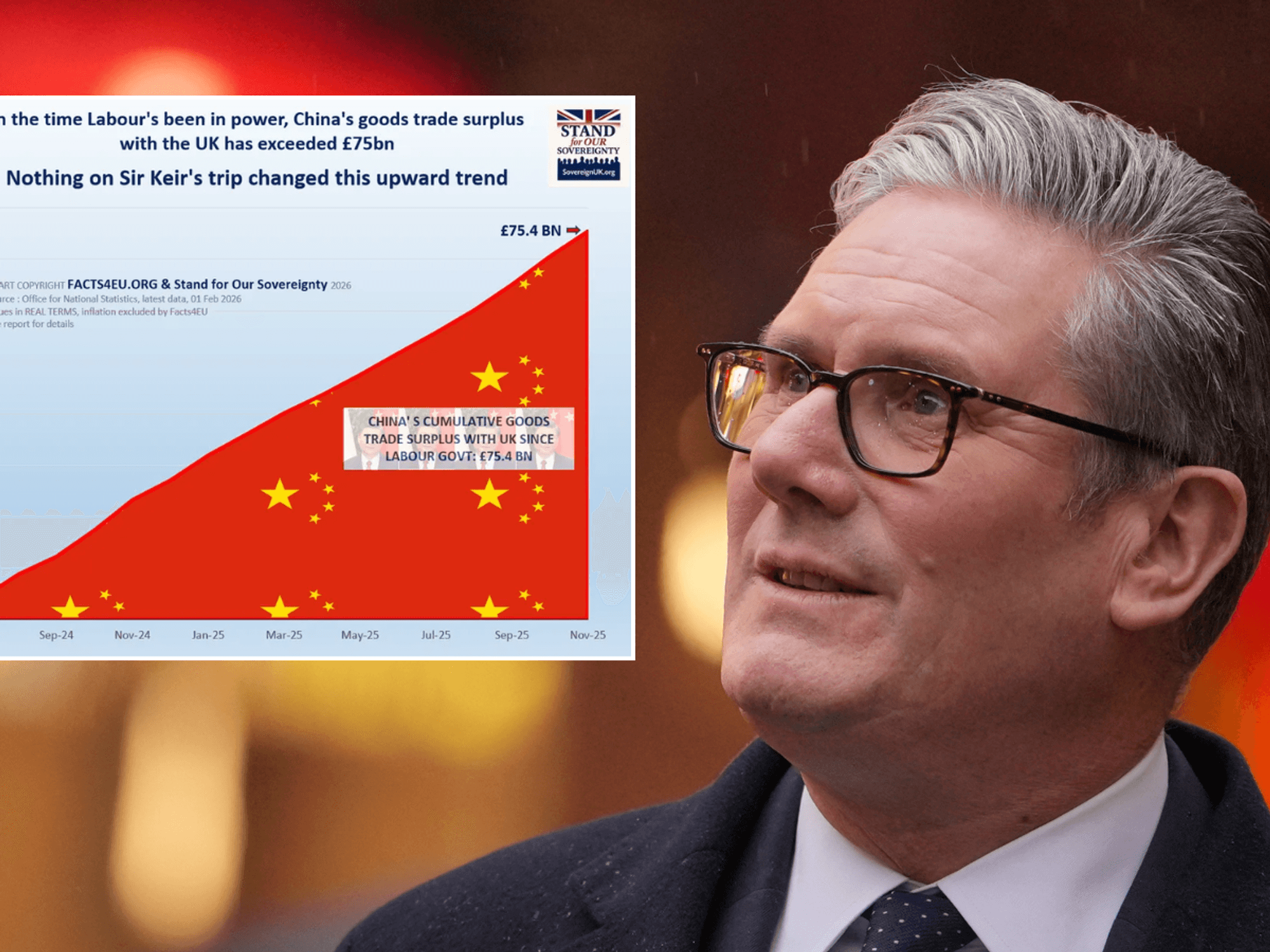

The backlash against globalisation, a phenomenon which once seemed unassailable, will continue apace, as voters across Western nations, having seen the damage that unfettered international markets can wreak on their communities, reassert their belief in national sovereignty.

Meanwhile, more radical elements on the Left will be drawn to Zack Polanski’s Green Party and its Corbynite programme of reordering the economy away from the interests of the wealthy few and towards the many. Such a message will always be seductive to those for whom the economy long ago stopped working.

But the Greens’ insistence on peddling the extremes of cultural progressivism – and especially their mad belief that a woman can have a penis – will see to it that they never attract a sufficient number of mainstream voters to become a major political force.

With our communities divided more than ever along ethnic, religious and cultural lines, the communal sectarianism that we have seen emerge on our streets, much of it the fall-out from conflicts in foreign lands, is unlikely to abate.

Against this whole backdrop – economic stagnation, porous borders, failing public services and gradual social disintegration – it is hard not to conclude that the established order is under threat in a way not seen for generations.

The year 2026 may prove era-defining. Buckle up.

More From GB News