GBN Health Check: Is stress increasing your risk of cancer? Here's what oncology experts say

Stress has been linked to the initiation and progression of cancer

|Getty Images

In this week's GB News Health Check, GB News.com's Health Editor Adam Chapman explores the complex relationship between stress and cancer

Don't Miss

Most Read

Latest

What humanity has achieved in the last two hundred years is breathtaking.

In 1820, nearly 84 per cent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty.

The latest World Bank assessment puts the current figure at 8.5 per cent - a reduction of more than 70 per cent.

Over this same period, global vaccination and literacy rates rose sharply, the number of children dying before their fifth birthday plummeted and democracy proved contagious.

And thanks to the convergence of technological and scientific advancements, many of these trends are accelerating.

Humanity's biggest battle is yet to be won, however. Despite billions in funding, a cure for cancer remains out of reach and the world is paying a heavy price.

In 2022 (the latest year for which data is available), there were an estimated 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million deaths.

Cancer rates are also trending in the wrong direction. GB News has previously reported on the rise of cancers in young people, for example.

There are grounds for optimism. Personalised mRNA cancer vaccines and other immunotherapy treatments are starting to come online.

And scientists continue to advance our understanding of the complex processes that cause cells to divide and multiply.

We now know for sure that processed meat is a cause of cancer, for example, but many risk factors are not well understood.

The role that stress plays in the initiation and progression of cancer falls into this grey zone.

Research has not established a causal relationship between the two so it is given short shrift from public health bodies.

Megan Winter, health information manager at Cancer Research UK, told GB News: "Stress does not directly increase the risk of cancer. However, people respond to stress in different ways, and some may find it harder to keep healthy during stressful times. Some people may opt for less healthy foods when they are stressed, smoke, or drink alcohol. These things can affect cancer risk.

"There are proven steps that you can take if you are concerned about your risk of cancer. These include not smoking, keeping a healthy weight and cutting down on alcohol."

Professor Melanie Flint of the University of Brighton and others have looked specifically into stress and cancer risk.

The Professor of Stress and Cancer Research is actively researching the direct interplay between the hormones cortisol and noradrenaline and the immune and cancer cells.

Stress hormones are highly potent and can interact with almost every cell in the body including normal, cancer, and immune cells, she explains.

Professor Flint, formerly at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, has shown through her research that DNA can be damaged as a result of stress, leading to cell transformation.

Since her breakthrough research was published, prof Flint has been leading further investigations to understand in depth the role that stress can play in patients’ responses to the disease and working towards programmes of treatment that take this into account.

Research has shown that DNA can be damaged as a result of stress, leading to cell transformation

|Getty Images

Breaking it down

It's important to understand the effects of stress and the role it plays in the body.

Stress can be defined as a state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation.

It is a natural human response that prompts us to address challenges and threats in our lives. Everyone experiences stress to some degree.

According to Professor Flint, exposure to stress produces a physiological response. This involves the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (a communication system between three organs) and the sympathetic nervous system.

"Mediators of this stress response are the hormones cortisol and catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline), that stimulate the adrenergic pathway. These can produce acute stress or chronic stress depending on how long a person is subject to the source of the stress and, although the body will adapt, prolonged stress can cause hyper-responsiveness to stressors and long-term damage to brain tissues."

According to the professor, these "chronic stressors" might be situations such as caregiving, bereavement, social isolation, the news that a patient may develop cancer, or the process of cancer treatment.

Over time, these stressors generally result in an "increased and continued release of stress hormones that may favour tumour initiation", the cancer researcher adds.

Evidence supports her conclusions. There are studies linking stress to tumour growth in patients who already have cancer, for example.

Correlation is not causation, of course, but the cancer journey is incredibly stressful so it merits further investigation.

Stressing the point

Doctor Kiran Dintyala, aka 'Doctor Calm', has devoted his professional life to getting into the minutiae of mood changes.

As CEO and President of Stress Free Revolution, he provides sufferers with practical tools and exercises to help them combat stress.

He is adamant that stress is a "silent killer", citing research papers that he claims demonstrate the various ways stress can directly or indirectly increase the risk of cancer.

One way this happens, the doctor claims, is through inflammation.

Inflammation is the body's response to tissue damage, caused by physical injury, ischaemic injury (caused by an insufficient supply of blood to an organ), infection, exposure to toxins, or other types of trauma.

According to one research paper, published in the Annals of African Medicine, the body's inflammatory response causes cellular changes and immune responses that result in the repair of the damaged tissue and cellular proliferation (growth) at the site of the injured tissue.

Inflammation can become chronic if the cause of the inflammation persists or certain control mechanisms in charge of shutting down the process fail, the authors write.

When you’re in a constant state of stress and your fight or flight system won’t shut off, the body’s inflammatory response may become chronic too, which may lead to cancer growth or spread, the thinking goes.

According to Doctor Dintyala, when chronic stress triggers an inflammatory response, it impairs immune function by suppressing T cells, which are essential for mounting immune responses against cancers.

This is not a fringe view; we know that the immune system is directly disrupted by the endocrine response to stress.

And when the immune system is not functioning properly, you are at an increased risk of developing cancer as well as infections, warns Macmillan Cancer Support.

The other route is via catecholamines - hormones that play a critical role in the body’s “fight or flight” response to stress.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS

The body’s inflammatory response to stress may become chronic

|Getty Images

The devil is in the detail

The stress doctor cites evidence suggesting that chronic stress and the associated release of catecholamines may increase the risk of developing certain types of cancer and promote the growth and metastasis of cancer cells.

This link was compelling enough for the National Cancer Institute (NIH) to conduct a report into the matter, unearthing evidence from experimental studies suggesting that "psychological stress can affect a tumour's ability to grow and spread".

The NIH cites several studies that have linked stress to cancer.

One case-control study among Canadian men found an association between workplace stress and the risk of prostate cancer, whereas a similar study did not find such an association

In a 2008 meta-analysis of 142 prospective studies among people in Asia, Australasia, Europe, and America, stress was associated with a higher incidence of lung cancer.

A 2019 meta-analysis of nine observational studies in Europe and North America also found an association between work stress and the risk of lung, colorectal, and oesophagal cancers.

Again, associations do not prove causation but the studies are striking.

In a review of 18 studies involving 406,210 participants, individuals with two or three kinds of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) were 35 per cent more likely to develop cancer and individuals with at least four ACEs were 117 per cent more likely to develop cancer than individuals with no ACEs.

Of the different types of ACEs examined, physical abuse (23 per cent higher), sexual abuse (26 per cent higher), exposure to intimate partner violence (26 per cent higher) and financial difficulties in the family (16 per cent higher) were associated with the risk of any cancer.

It is unclear whether treatment for the long-term impact of ACEs-related stress could reduce the risk of cancer.

Recent molecular and biological studies also sugguest another possible mechanism: specific signaling pathways that influence cancer growth and metastasis.

As Dintyala explains, stress hormones can inhibit a process called anoikis, which kills diseased cells and prevents them from spreading. This in turn provides a "mechanistic advantage" for metastasis, he says.

Essentially, the claim is that chronic stress fosters the growth of tumours via stress hormones, inflammation, and immune suppression.

Doctor Fern Kazlow, a psychotherapist and holistic health expert, needs no convincing.

She is currently living with cancer and has seen countless patients with cancer over the course of her 35-year career.

"We're wired to keep our body and cells healthy, to not let them become cancerous. To heal our body. When you have stress, it can topple everything over," she told GB News.

The psychotherapist expresses frustration at what she views as the myopic thinking behind much of Western medicine.

As she sees it, the body is a complex interplay of forces and we should look at how all the parts interact.

In addition to stress-induced inflammation, Doctor Kazlow believes patients have a better chance of putting their cancer into remission if they can find ways of relaxing.

There's no evidence to support this claim but a study does suggest that stress hormones may wake up dormant cancer cells that remain in the body after treatment.

In experiments in mice, a stress hormone triggered a chain reaction in immune cells that prompted dormant cancer cells to wake up and form tumours again.

But if you are stressed, that doesn’t mean your cancer is going to come back, said the study’s lead researcher, Michela Perego of The Wistar Institute Cancer Center.

Several intermediate steps need to occur, Doctor Perego adds, at least according to his studies in mice.

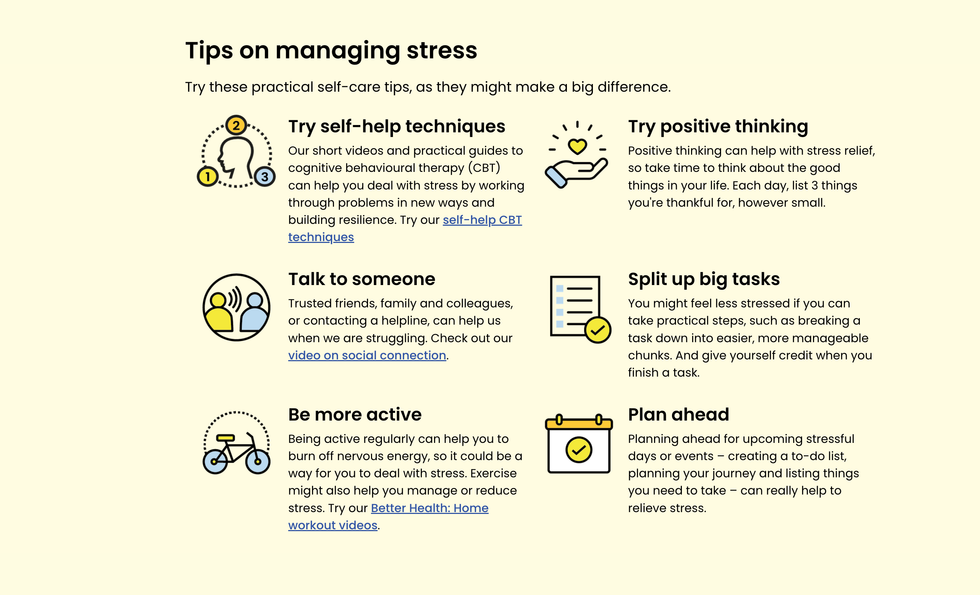

Top tips for managing stress include splitting up big tasks and talking to someone

|NHS

Don't panic

There's plenty of pushback to all of this and definitive conclusions cannot be drawn.

There are also numerous ways to modify the risk of cancer.

As Sean Marchese, a registered nurse at The Mesothelioma Center with a background in oncology clinical trials puts it, any link between stress and cancer remains one of the "more complex and less well-understood areas of scientific study".

He concedes that extended periods of secretion of cortisol and adrenaline could "theoretically" support tumour growth with ease through impairing immune function and encouraging other behaviours like smoking and poor dieting, "direct evidence linking it as a sole causative agent for the origin of cancer is lacking".

Stress may, however, play a role in the progression and metastasis of cancer, in which it would potentially advance the cancer rather than initiate it, he acknowledges.

Epidemiological research is still "inconclusive", the oncology expert adds, noting that some results show higher cases of malignancy in highly stressed people, but most of the studies were not able to distinguish the role of stress or its associated unhealthy behaviours.

Other studies suggest interventions targeted at enhancing stress management and improving attitude may benefit prognosis in patients with cancer, but the evidence is "limited", he tells GB News.

"There are multiple biological, behavioural, and psychological mechanisms at play in the relationship between stress and cancer, so more research is needed to fully explain the relationship."

Others are less charitable. Cancer Research UK brands any talk of a causal association between stress and cancer as a "myth".

The best quality studies have followed up on many people for several years. They have found "no evidence" that those who are more stressed are more likely to get cancer, reports Cancer Research UK.

For example, a meta-analysis of 12 cohort studies in Europe found no link between work stress and the risk of lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancers.

A prospective study among more than 100,000 UK women reported no association between the risk of breast cancer and perceived stress levels or adverse life events in the preceding five years.

Cancer Research UK does acknowledge that it "can be harder for some people to keep healthy during stressful times, which can lead to an increased risk of cancer".

Knock-on effects

Extensive evidence suggests stress leads to habits that directly increase the risk of cancer.

Stress is a significant risk factor for cigarette smoking, for example.

In one study, published in the journal Addictive Behaviour, a "strong positive association" was observed between perceived stress and nicotine withdrawal symptoms in smokers of both sexes, with a larger effect seen in women.

"These findings emphasise the importance of stress reduction in smokers, which may lead to fewer withdrawal symptoms and more effective smoking cessation," the study's authors wrote.

You can get support and tips for quitting smoking here.

Another study, published in BMC Psychology, noted that stressful experiences are "important risk factors" for excessive alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders (AUD).

Alcohol is a proven risk factor for cancer.

The NHS urges everyone to drink within the recommended guidelines of no more than 14 units of alcohol a week, spread across three days or more.

Furthermore, researchers have found an association between ultra-processed food consumption and perceived stress levels in workers, and the effect cuts both ways.

They found that workers who consumed ultra-processed foods had significantly higher perceived stress levels and higher perceived stress levels were associated with increased odds of higher ultra-processed food consumption.

The finding is significant because processed foods such as ice cream, sandwich ham, crisps and biscuits can lead to weight gain - a major risk factor for cancer.

In fact, being overweight or obese is the second biggest cause of cancer in the UK – causing more than one in 20 cancer cases.

Processed meat in particular has been classified in the same category as causes of cancer such as tobacco smoking and asbestos.

Remember, when it comes to cancer risk, the most important thing is to aim for a healthy, balanced diet.

According to Cancer Research UK, that will probably always contain the occasional less healthy or ultra-processed food, but as long as you’re eating lots of wholegrains, fruits and vegetables and keeping a healthy weight, there’s no need to worry.

Drinking too much alcohol increase your risk if cancer

| PAAaaaaand breathe

Reducing your stress levels will also provide a buffer against these unhealthy habits.

If you’re struggling to cope with stress, it’s a good idea to speak to your doctor.

You can find information and tips about coping with stress on the NHS and Mind websites.

"Some of them you'll find really annoying, some of them you love, but those will use your mind to help relax your body," she told GB News.

Doctor Kazlow is a big fan of breathing exercises too: "There is a very common breathing exercise that's called 4 7, 8, and there are others you can look up, but this is a really easy one."

How it works:

- Take a breath in over the count of four

- Hold it for the count of seven

- Exhale for the count of eight

"It's really simple and you can do that throughout the day. You can do it when you feel anxious. It will reset your nervous system. So even if your mind is going crazy where it's very hard when people say, 'just think positive'. You need to create the conditions for positive thinking to be able to live truly," the psychotherapist tells GB News.

The NHS also recommends the following:

- Try self-help techniques

- Talk to someone

- Be more active

- Try positive thinking

- Split up big tasks

- Plan ahead